Emos vs. punks : Radio Ambulante : NPR

REPORTER: The appointment was at three in the afternoon at the Glorieta de Insurgentes. Young self-styled emos were gathered to demonstrate and defend their ideology.

DANIEL ALARCÓN: What you are listening to is a TV Azteca report.

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVE)

GROUP: Emos, emos, emos, emos!

ALARCÓN: For those who don't know or need a reminder… Let's review: in the 90s there was talk of urban tribes, groups of people, especially young people, with similar tastes. One of those tribes were the emos.

Let's see…they were teenagers dressed in dark colors, sometimes pink, striped shirts… skinny jeans. Their long hair fell over their foreheads, covering their eyes...

Emo stands for emotion. His philosophy, if you can say philosophy, was to feel… and feel a lot. A very adolescent thing. If I were a little younger, surely I would have identified with them. They expressed a half-theatrical sadness that was reflected in their aesthetics and especially in their music.

So, that day at the Glorieta de Insurgentes, they demonstrated because their nemesis had arrived...

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVE)

REPORTER: The threat was from groups called punks and it was. They came screaming.

PUNKETOS: (intelligible screams).

ALARCÓN: The punks, or punketos as the reporter calls them, are much better known… Anarchy, chains, heavy music, piercings, leather jackets and military boots. And the hairstyles, of course… Mohicans that fought against gravity.

The thing is, the punks weren't happy with the emos for reasons you'll find out later. But one group dedicated itself to organizing a beating online.

They put a time, date and even a slogan for the event: "Make a country and kill an emo." Emos were used to brutal bullying, but on that very day, at the Glorieta de Insurgentes, they did what no one expected... They defended themselves.

And that is what we are going to tell you today: the story of one of the strangest battles that Mexico City has experienced: the emos vs. the punks, and the consequences that this confrontation had on the countercultural scene in that country.

Within the Radio Ambulante team there is a person who remembers very well everything that happened. Our production assistant, Fernanda Guzmán.

After the break, Fernanda tells us.

[MIDROLL 1]

FERNANDA GUZMÁN: First of all, I want to clarify something. I'm going to talk about injuries and resentment, about street fights, unnecessary hatred, even gratuitous. But still - and this will sound strange - many of us who remember that battle have some affection for it. It was the little guy defending himself against the big guy, the bully… There's always something inspiring about that.

When emos were all the rage, in the mid-2000s, I was in high school. It's been over a decade, it feels like it's been an eternity. And it is that being a teenager then was very different from what it is now.

For example, information did not circulate like it does today. The internet was just beginning to be an everyday thing for teenagers in Mexico. Do you remember the phones of that time? With keys, cameras of very low quality, some still had antennas that you had to take out to have a signal... And to play music you had to use completely obsolete technology, such as infrared.

Facebook and Twitter already existed, but they weren't that popular. What was used was My Space, Hi 5, Metroflog. Before we talked about something going viral, jokes and gossip were spread via email chains with comic sans fonts, garish colors, and computer viruses. It was a slower and... in many ways, simpler life.

Half of my school was or wanted to be emo, and the other half was bullying them. It was the order of things. Simple.

But being emo had its charm. That theatricality, that feeling emotions without any filter, that going against what we are told is the norm... In adolescence they are things that catch you, that you even need.

Here's a confession: I did not escape that charm. Although I didn't want to admit out loud that I liked emo, my hair just happened to always cover one of my eyes. But yes, whoever asked me said: "No, I'm not emo, what's up." I tried to talk about it once with my dad: "And if I were emo, what would you think?" I asked him. "Don't classify yourself," he told me.

Although classifying is part of seeking identity, at least initially. And everyone at my school was doing it. Most of them were emo. I also remember the skaters, the metalheads, the strawberries, some rockers… There was everything.

But this story is not about me, about those of us who didn't know if we wanted to be openly emos or not. It's about those who did carry the label with pride. I present to you one of them: Ollin Sánchez, better known at the time as “el Mosco”.

OLLIN SÁNCHEZ: My first contact, so I got to know about emo, was when I entered high school. I was, I think, about 15 years old, 16...

GUZMÁN: This was in 2006 when there were still no fights or enemies of emos. Ollin was, so to speak, one of the first waves of emos of the two thousand in Mexico City.

SÁNCHEZ: Well, that was almost in its infancy, the emo thing. There we were inventing him and…

GUZMÁN: At that time not much attention was paid to them. They were small groups of friends who talked about music, about their lives… who drank in secret and wandered down the street together to hang out. The teenage dream.

To create their aesthetic, they imitated the style of the bands they liked, took ideas from their friends' clothes and also looked for inspiration through MySpace. There were pictures of emos from other countries, especially from the United States, showing their hairstyles and their way of dressing. And especially the music...

ALEJANDRO CASTILLO: In fact, MySpace was the place where you met the bands. And you could get music from them.

GUZMÁN: He is Alejandro Castillo, the “Bake”, one of Ollín's best friends at the time. He was a fan of Japanese culture, especially music. And the emo aesthetic caught his attention.

CASTILLO: Tube pants, black shirts, eyeliner. Let's say looking a... a bit androgynous and that's what I found in Japanese groups...

GUZMÁN: There were also the referents from the United States: My Chemical Romance, Paramore, Fall Out Boy… And other Latins: PXNDX, Delux, Kudai… many pop punk, metal, screamo and post-hardcore bands, which is this rock genre with guttural and dramatic screams, Alejandro's favourite.

CASTILLO: Yes, there are things that at one point you want to express and you don't find the best way to express them, as they say: you would like to shout.

GUZMÁN: Unlike punk, which usually talks about rejecting the system and politics… the lyrics of the music, in quotes, emo spoke more about intimate conflicts, about our emotions, of course.

Over time, emo fashion became widespread. They were no longer little balls of friends isolated in schools here and there. Suddenly the shopping malls, the parks, the public squares... the streets in general were full of emos. Nobody knew where they came from, but cities around the country were being taken over by teenagers with long bangs.

The emos adopted specific points of the city to turn them into dens.

SÁNCHEZ: The first place where we started to get together was in El Chopo.

CASTILLO: I began to get together with a group of friends in El Chopo. El Chopo is here a flea market in Mexico City that is held on Saturdays.

GUZMÁN: El Chopo is a street market with dozens of stalls selling small talk, clothes, accessories and most importantly: music, lots and lots of music. Not only is it sold, albums are also exchanged, concerts and cultural events are organized.

DANIEL HERNÁNDEZ: El Chopo is historically, since the eighties, where all the subcultures of young people in Mexico meet. The different countercultures, the banditas, come together and link up: the punks, the skatos, the rappers, the pachucos.

GUZMÁN: This is Daniel Hernández. He is a journalist, now he works at the LA Times. But at that time he wrote about the subcultures of Mexico City. And at the time when the emos began to visit Chopo, he spent there investigating.

HERNÁNDEZ: And suddenly it was seen, I saw it with my own eyes, as a new wave of fashion mainly, of these kids who made their fringes very high in the back or in the front like that.

GUZMÁN: And this look caught my attention...

HERNÁNDEZ: In other words, from the groups that were already more, or are more established: the goths, the punks or the skinheads or those like that, hardcore rockers… the emo, yes, it was kind of funny.

GUZMÁN: They were a poor parody of themselves. An attempt to copy something from everyone and not get anything of their own.

HERNÁNDEZ: So it was… um… here you feel a bit of social tension.

GUZMÁN: For the vast majority of these established groups, emos were superficial children and nothing more, but some took it personally. That's why the anti-emo movement started: with calls to beat 'em up and everything else. And the first place they wanted to kick them out of was, precisely, El Chopo.

This is Ollin.

SÁNCHEZ: We were not well received, that's how you arrived and… and harassment and rudeness. And just like they kicked us out, that is, they kicked us out like this: “You can't be here, go away”.

GUZMÁN: So they had to give up Chopo. These are some of the antiemos of the time speaking in television interviews:

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVE)

PUNK 1: That's not movement, that's not culture. You talk to me about culture, I'm Mexica.

PUNK 2: No, because they are discriminated against. They take depression as their main ideology, and depression is not an… an ideology, it's a disease.

PUNK 3: They're taking things from different cultures and they don't even know what the hell is going on (censorship beep). They don't know, they haven't started to investigate what the hairstyle means, what the boots mean, they don't know anything. They are drinking just for fashion. A few years ago there weren't and now, even if it goes by, you find fifty emos a day.

GUZMÁN: Over time, the atmosphere of tension against the emos grew: outside Chopo and outside the schools... A key moment in this transformation was when this monologue was broadcast:

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVE)

KRISTOFF: Emo sucks. What is emo? It's a fifteen-year-old girl thing.

GUZMÁN: This is Kristoff, a presenter on Telehit, one of those ordinary music channels that tried to aspire to have a style like MTV. The channel was very influential among teenagers… Its presenters were public personalities and what they said was relevant… That is why the weight of Kristoff's words, who was one of the stars…

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVE)

KRISTOFF: They just got excited because they love the singer in the band, not because they like the music. Number 1, number 2, is it necessary... necessary to create a new genre to express emotions? Doesn't death metal help us? Aren't we enough with punk? ?

GUZMÁN: As part of his investigation, Daniel Hernández was able to talk with him. This was his reaction when he remembered it:

HERNANDEZ: Kristoff (laughs). Oh no, Kristoff.

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVE)

KRISTOFF: It is necessary to create a new genre that says: “Dude, everyone else is wrong, they don't fulfill us emotionally” Fucking bullshit children, there is no movement, there is no way of thinking, there are no musicians.

HERNÁNDEZ: Kristoff was, yes, a… a very macho presenter, like… like very rock, right?, mainstream rock, but who thinks he is… alternative? (laughs).

GUZMÁN: That image, the one interpreted by Kristoff, was the one that some rockers wanted to maintain, especially the anti-emo: strong, rude, superior… annoyed with these emotional teenagers. The monologue that Kristoff did that day became what would now be called viral, it reached a lot of people.

HERNÁNDEZ: And with that clip I think a lot of other Mexicans and young people who weren't emos felt, uh, supported, they felt inspired to take Kristoff's words and apply them directly to emos in whatever town they were.

GUZMÁN: Ollín and Alejandro say that after being exiled from El Chopo they looked for another place to make it their meeting point. One of his friends invited them to the bar where he worked: Los Sillones.

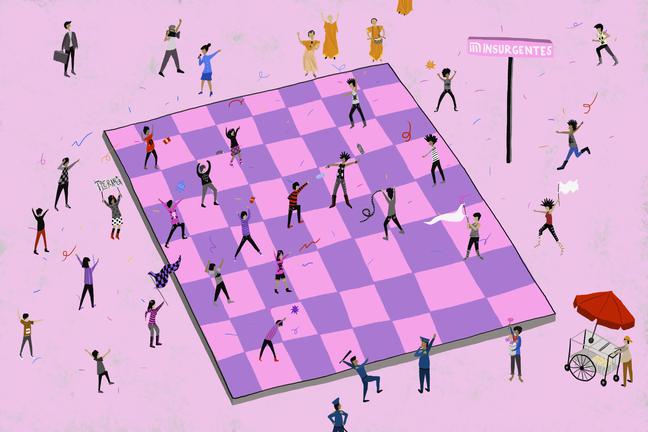

It was a tiny bar that sold beer, played the trendy music of the time, and was one block from the Glorieta de Insurgentes. And for those who have never visited Mexico City, I will tell you what the Glorieta is like. It is a large open-air circular plaza, where thousands of people walk daily. On the shores there are many places of food, clothing, pharmacies, internet cafes, and back then, even a video game machine stand. It is always busy because it is the exit of the Insurgentes subway station, one of the most important and central in the city.

And well, the bar was called Los Sillones because it was literally a place that only had a couple of armchairs to sit and drink. Nothing more. It was quite seedy, that is, neglected.

SÁNCHEZ: In other words, all… all the people came to the Glorieta because few of us came to the famous (sic) armchairs, which was like a… a little place that later became like a clandestine bar, or something like that, because, well, we were all underage. age and there we drank.

GUZMÁN: You can imagine why it was popular. Los Sillones became the new exclusively emo meeting point. Of course they didn't have a sign on the door saying that only emos could enter, but the appropriation of the place was clear. Daniel Hernandez, for example...

HERNÁNDEZ: I was never able to get into Los Sillones, the net couldn't get in. I felt like it was a place where you literally had to have fringe to get in and… (laughs).

GUZMÁN: So the emos began to meet at the Glorieta to go from there to Los Sillones. And since it was too small a place for an army of emos, it was always packed. Many did not enter the speakeasy and stayed to hang out in the Glorieta, talking and listening to music.

That square and that bar became a refuge for emos, a place where nobody bothered them at last, where they had a second family of friends, which at that age is very important. And where they could finally just be.

HERNÁNDEZ: There was already a geography, do you understand me? There were already places where this new little group could already claim some public space. And for me, Mexico City is always an issue of conflict over public space. It's always a theme, right? In the city.

GUZMÁN: In the eyes of the most dogmatic punks and anti-monsters, this was a threat. They were no longer, in their words, copying the style, now they were also appropriating the spaces in the city. So they were not going to give up the Glorieta so easily. Once again Ollin.

SÁNCHEZ: There were punks going to the Glorieta to… they… they said to cut their hair. I mean literally: they did go and cut your fringe.

GUZMÁN: They were persecuted…

SÁNCHEZ: And whoever they caught, they beat him and cut his fringe.

GUZMÁN: In addition to the beatings, cutting their hair was extremely violent for me. Keep in mind that the emos were teenagers from 13 to 17 years old, while the punks were older, young people in their twenties messing with pouts, children.

While emos were still a massive fad, no space they embraced across the country was a safe place for them. With the help of the internet and the media, emo hatred was no longer a small matter.

HERNÁNDEZ: And just in many other cities throughout Mexico suddenly there are a lot of emos and also a lot of people saying or declaring themselves anti-emo.

GUZMÁN: They organized themselves for such and such a day and time to go out and beat up the emos. One of the first times was in Querétaro, about two hours from the capital.

This is Alexander.

CASTILLO: Some were already scared because a video of Querétaro had been shared where they beat up some emos boys in a square.

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVE)

ANTIEMOS: He wants to cry, he wants to cry, he wants to cry!

CASTILLO: So you know, fear, right?

GUZMÁN: I remember the fear. For me, it came with a video that a stranger shared on the cell phones of my entire class. A young woman was seen being hit on the head with a brick. No one had to explain the context to me. From her appearance…her hair, I understood that the girl was emo. We are all shocked. It was the topic of conversation the entire day and also one of the main reasons I decided not to be emo, even though I loved the style. It was until now, investigating this story, that I found out that the video was, in fact, from the Middle East and not from Mexico. But the level of persecution this group had made it seem completely viable in my country.

The first video, the one that was of the beating in Querétaro, was broadcast in Mexico City with the threat that it would be repeated here. An image with a black background and white letters began to circulate on My Space and by email, reading: "Make a country and kill an emo."

Due to incidents like the one in Querétaro and the calls for violence that circulated on the internet against emos, it felt like things were getting out of control.

Even Kristoff himself, who had previously made fun of emos, now came out to try and calm things down a bit. In his way.

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVE)

KRISTOFF: Why do they mess with emos? They mess with the emos because the emos don't defend themselves dude, because they're in their fucking fart. Leave them bastard, what's the fucking fart? What balls do they have to get together over the internet dude and fuck three poor emo bastards. What cock did these kids give them? What blowjob did these kids give them?

GUZMÁN: And he closed with this:

KRISTOFF: I may not agree with what emos think or with what other people think, but I would die, you bastard… I would die to defend the right that those bastards have to express themselves. Thank you. mothers! (applause) fucking stupid people…

GUZMÁN: But it was already too late. A call had been formed for a beating in Mexico City on Saturday March 15, 2008 at 3 in the afternoon, in the Glorieta de Insurgentes. It was only a week after the incident in Querétaro.

That Saturday afternoon was clear and cloudless. One of the people in the Glorieta de Insurgentes that day was him.

SALVADOR CASTRO: My name is Salvador Castro. I'm from here in the City. I am 32 years old.

GUZMÁN: Salvador, who was 19 years old at the time, and one of his friends had agreed to go play slot machines at one of the local stores. Neither of them were emo as such, but they enjoyed the same music and aesthetics, so they knew the emos and the punks well. Salvador's friend tried to warn him, telling him that there would probably be a conflict that day and that they had better go somewhere else, but Salvador reassured him.

CASTRO: There's not going to be… there's not going to be anything. Three fucking metalheads are going to arrive wanting to fuck ten guys. And the other guys are not going to do anything. In other words, they're just going to yell.

GUZMÁN: While they were playing arcade games, little by little the Glorieta began to fill up, even more than usual. If on a normal day there were between fifty or a hundred emos, that March 15 there were more than two hundred...

CASTRO: And we went out and started seeing…too many already…there were too many emos. If it was like hey… well there's going to be a gig, or what's up?

GUZMÁN: Tocada means concert. That afternoon, Ollín and Alejandro were in the Armchairs. Alejandro had prepared a party for that night, and they were looking forward to it. They tried to relax like any other Saturday, but they couldn't ignore the tense atmosphere. Many in the bar were afraid that the punks would show up.

SÁNCHEZ: The truth is, I didn't take it like that… like very seriously, I thought it wasn't going to happen. We were in this bar that I'm telling you, Los Sillones, when… when they began to say yes… that they were coming.

GUZMÁN: The emos that were in Los Sillones got up and joined the rest that were outside. They began to talk until they were interrupted by a noise: from one of the entrances to the Glorieta they could hear screams approaching in the distance.

CASTRO: In that we see that some… some darketos and some metalheads came, with some punks who brought some chains. And I did tell him: "ah, don't stain, I think there will be a fart, dude." My friend told me: “No, don't stain”. "No, well, I'm calling you bastard."

GUZMÁN: La Glorieta split into two groups. The emos and the punks. The advantage of the emos was that they were vastly outnumbered: there were less than 20 anti-emos, mostly punks and metalheads, against more than 200 emos.

One of Ollín and Alejandro's friends tried to avoid the confrontation, approached the opposing group and told them:

CASTILLO: What, what do they want there, right? What are they bothering? That we are not doing anything, that they should leave.

GUZMÁN: But despite seeing themselves at a disadvantage, the punks didn't intend to back down. They threatened them with shouts.

CASTRO: They started yelling, they were yelling at each other: “No, well, I'm going to beat the crap out of you, I'm going to kill you. They're going to see right now sons of bitches." And the… the emos said like: “Well, camera, man, then get down”.

GUZMÁN: “Camera” is like saying “then go ahead”. The police approached the area to try to impose peace with their presence and prevent the situation from ending in blows. But nobody cared.

Quickly a group of emos searched the floor for anything to defend themselves and push the punks back.

CASTRO: And they were throwing bottles…garbage. In general, garbage was thrown.

GUZMÁN: A television reporter had already arrived at the scene and her cameraman was recording everything that was happening.

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVE)

REPORTER: The emos responded by throwing bottles that hit part of the other gang.

GUZMÁN: With this, the first wave of blows began. Ollín stood in a safe area trying to avoid the attacks. But Alejandro ran after one of his friends to defend him, and managed to free him from one of the punks.

CASTILLO: I arrive behind my friend, I pull him. And well, now yes, just like that in the heat of what happened, I came and hit the other one and he fell with his girlfriend.

GUZMÁN: Salvador couldn't believe that the emos teens were hitting back.

CASTRO: And it was like very... very strange to see... to see them as sensi...being aggressive, right? to all the emo kids.

ALARCÓN: And in everyone's eyes, emos were docile. But well, there they were, responding to the attacks to the surprise of the spectators, and of course, of the punks.

And the battle was just beginning.

A pause and we return.

[MIDROLL 2]

ALARCÓN: We're back at Radio Ambulante, I'm Daniel Alarcón.

Before the break, we heard how the harassment of emos in Mexico had been growing for years… Until it all exploded in March 2008, with violent attacks in several cities, and a battle between urban tribes in the Glorieta de Insurgentes, a very crowded and central to Mexico City. Bottles and garbage flew through the air like projectiles. The punks, who had come to attack the emos, were, to their surprise, cornered.

But the battle continued. No one was willing to give up.

Fernanda keeps telling us...

GUZMÁN: After beating a punk to the ground, Alejandro crossed the battlefield and returned with Ollín and his group of friends. The plan was to defend themselves as best they could from the punks, who far from giving up, kept fighting and throwing insults. This is how Alejandro and Salvador remember it…

CASTILLO: Fucking emos, assholes, whores and things like that...

CASTRO: "Now you're going to see son of a bitch, I'm going to bust your fucking snout, you fucking emo." I remember that just like how I heard it because I even turned to see the metalhead of “ah, hey dude, calm down”.

GUZMÁN: Eventually both sides ran out of power and everyone needed a little air. There were insults traveling from one side of the Glorieta to the other, but the blows stopped.

CASTRO: They had taken it as a break because everyone was tired of fighting with everyone and they were there as if licking their wounds.

GUZMÁN: It was a moment of truce and the police took advantage of the pause to try to disperse both sides. Two hours passed, long enough for everyone to think that the conflict was over. But the peace was momentary. Out of nowhere, someone dropped a belt and then...

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVE)

REPORTER: The second confrontation…(Sound of conflict in the background). The women of both sides were transformed into beasts. They were ready with belt in hand, suddenly...

GUZMÁN: During the break, the punks got reinforcements, but the emos were still the majority. Let us remember that they had suffered years of bullying and harassment. It got to a point where the only thing everyone needed was to get even, it didn't even matter against whom anymore. The blows no longer responded to sides.

CASTRO: It started to be like a pitched fight where they were already beating everyone, that is… everyone against everyone.

GUZMÁN: Eventually the police took control of the situation to separate them and surrounded both the emos and the punks, but they didn't really know what the conflict was about or who was fighting...

In the report they interviewed a police…

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVE)

POLICE: People of another belief were detected there, of another cult that we prevented from coming together so that there would be no aggression from both parties.

GUZMÁN: They couldn't hit each other anymore, but the tension and the shouting continued from a distance. Finally, what worked to dissolve the conflict was an unexpected distraction…

REPORTER: Suddenly, as if it were a joke or a surreal movie, songs and music were heard coming from the insurgent subway. It was a group of hare krishna and believe it or not they scattered the attention.

GUZMÁN: They were men with orange and white tunics… Every Saturday they put on a musical show at the Glorieta de Insurgentes.

SÁNCHEZ: They got there and sort of calmed down the situation a bit… Rather, it got us out of the loop.

GUZMÁN: And among the bottles and garbage, chants and drums were heard while the police evacuated everyone. The place was finally deserted.

There were no serious injuries. Alejandro, Ollín, and Salvador returned home safely. But news of the beatings spread to the other subcultures of Mexico City.

DARYNKAYNA MARÍN: We all found out what was happening there and we said what's wrong with them, right?

GUZMÁN: This is Darynkayna Marín. She is 37 years old and since she was 16 she has been a goth… she dresses almost completely in black, with comfortable clothes or velvet dresses, stockings, boots and a lot of makeup. Much of her skin is tattooed. Her accessories are jewelry of skulls, bats and bones…

MARÍN: My curtains are purple, my furniture is black. Uh…very gloomy for ordinary people and maybe some people won't…they'll feel very comfortable here. Do not?

GUZMÁN: When she and her goth friends found out about the attacks on emos…

MARÍN: Here there was a great annoyance on the part of... the dark scene.

GUZMÁN: At that time, goths were known as darks, and until now the terms are interchangeable.

MARÍN: We used to meet at the Tianguis Cultural del Chopo. We met there every Saturday from 9 in the morning until 5 in the afternoon, making fanzines, making art proposals and so on.

GUZMÁN: And of course the emos conflict was a recurring topic of conversation at El Chopo. As members of the alternative scene, they felt very worried about everything that was going on.

MARÍN: The truth did come to the indignation that how was it possible if we consider ourselves empathetic people, that we also suffer some discrimination from sectors of society because of our way of dressing... And that they didn't... they didn't agree with our... our ideas that we had ingrained to attack other people for something so absurd that it is how they dressed, right?

GUZMÁN: But they remained observers from a distance… Until one day…

MARÍN: Ehhh… one weekend in El Chopo a lady arrives, who is also dark…

GUZMÁN: Her name is Angélica González or Angy…

ANGÉLICA GONZÁLEZ: My pseudonym Luna Negra, my age half a century… I'm from the old guard of rock and roll.

GUZMÁN: At that time I was 37 years old.

MARÍN: And she has three daughters. She… One is punk, the other is emo and the other is ska. And she is…well, she was the goth mom. A very alternative family that was highly appreciated within the Chopo community.

GUZMÁN: The daughter who was emo was 14 years old. At first Luna Negra would not let her go alone to the Glorieta de Insurgentes. To protect her, of course. She knew about the beatings, the fringe cuts, the insults and harassment, and she didn't want anything to happen to her.

But she did accompany her and there she got to know many of these adolescents well, she listened to them, guided them…basically she adopted them.

GONZÁLEZ: The time came when they called me the dark mom.

GUZMÁN: In fact, that Saturday of the battle at the Glorieta de Insurgentes, Luna Negra was there… she saw, indignant, the violence…

GONZÁLEZ: The badass groups of punks from… from yesteryear, they didn't go around with bullshit that “we're going to hit a child”. They were sheep, all those who hit the emos were sheep.

GUZMÁN: I mean, not real punks, but people who follow something for fashion, in this case beating up kids for fun.

GONZÁLEZ: Defend your country, chingá. He defends the repression against the people. What are you going to be fighting because they dress or don't dress? They are bullshit.

GUZMÁN: Her daughter wasn't hit in the Insurgentes battle, but she did hit him another time, while she was walking down the street with her friends.

GONZÁLEZ: And suddenly the whole band was there at El Chopo and some emos came running: “they hit your daughter”.

GUZMÁN: For her, that was the limit. No solamente porque golpearon a su hija ya sus amigos, sino que los medios también los señalaban a ellos, a todos los “punks y darks”, como los agresores.

La escena dark quería ayudar a los emos y desmentir que en su grupo fueran agresores… Aquel día en el Chopo, cuando llegaron a avisarle a Luna Negra que su hija fue golpeada, Darynkayna sintió que era momento de parar todo esto. Era 22 de marzo, una semana después del enfrentamiento en la Glorieta.

MARÍN: En ese momento agarré y le dije: ¿Sabes qué? Vámonos ahorita a la Glorieta de Insurgentes y vamos a hablar con los chavos.

GUZMÁN: Para decirles que era el tiempo de aclarar las cosas. Que ya basta de violencia y agresiones.

Así que se fueron en bola, varios punks, darks, góticos y metaleros con Luna Negra y Darynkayna hacia las tierras de los emos. Imaginen la escena: un montón de personas vestidas de negro, con estoperoles, esas púas que se ponían en la ropa los punks y los darks, con peinados extravagantes, botas y pinta de rudos caminando por Ciudad de México, enojados, indignados… Tan intimidante era su presencia que, llegando al metro, los policías los dejaron entrar gratis por miedo de que hicieran destrozos.

Eran como cincuenta y llenaron un vagón entero. A Darynkayna se le ocurrió una idea para asegurarse de que los emos no pensaran que los iban a llegar a agredir. Un símbolo de paz.

MARÍN: Una bandera blanca improvisada con una camiseta de mi esposo (risa) en un paraguas.

GUZMÁN: Pero llegando a la Glorieta muchos emos se asustaron y se dispersaron. Con prisa, Darynkayna, Luna Negra y los demás se acercaron a hablar con los que quedaban. Les explicaron que no todos los punks y darks tenían intenciones de golpearlos, que los apoyaban y querían ayudar.

La reunión comenzó a tomar forma de mitin político de grupos urbanos. Darynkayna se acercó a los periodistas que estaban ahí y tomó la palabra. Esta es una grabación de ese día.

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVO)

MARÍN: A eso venimos, a pedirles a ustedes que no tengan miedo de nosotros porque nosotros no venimos a agredir. Queremos platicar con ustedes para que se den cuenta de que nosotros jamás vamos a agredirlos físicamente, ni verbalmente ni de ninguna manera. Tanto punks, darks ni metaleros estamos dispuestos a que las televisoras TV Azteca, Televisa nos estén difamando. Que nos estén diciendo…

MANIFESTANTE: ¡No se vale!

MARÍN: … que nosotros somos agresores. Siendo que ellos siempre nos han satanizando.

MARÍN: ¡Bravo!

GUZMÁN: Se corrió la voz de lo que estaba pasando en la Glorieta y al lugar empezaron a llegarpersonas de varias colectivas LGTB que tenían ganas de ayudarlos. Y un representante del gobierno de la Ciudad de México. Entre emos, punks, darks, activistas y autoridades se hizo un diálogo a lo oficial, pero improvisado.

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVO)

MANIFESTANTE: Dark, emo, punk, rockabilly o lo que seamos… somos humanos… hay que respetarnos entre nosotros…

GUZMÁN: Esta es una chica emo…

EMO: Pues qué chido que vinieron y… qué chido, vamos a hacer las paces, ¿no? Y Vamos a unirnos contra el gobierno (risas). No, pero qué padre.

GUZMÁN: Se agendaron reuniones con funcionarios para que los grupos alternativos pudieran exponer sus preocupaciones y entre todos se buscara una solución al incremento de la violencia contra los emos.

Luna Negra y Darynkayna les propusieron a los chavos emos que organizaran una marcha para dar a conocer su postura y como un intento de defenderse de manera pacífica. Los darks también se ofrecieron a montar guardias en la Glorieta de Insurgentes para observar si se acercaba alguno de los punks violentos y ayudar a los emos a correrlos… En los medios lo informaron así:

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVO)

REPORTERA: Finalmente darks y emos hicieron las paces.

EMOS: ¡Tolerancia, tolerancia, tolerancia! (gruñidos)

MARÍN: Salió que ya no... ya habíamos firmado un tratado de paz… ¡hijos de su madre!, o sea, nunca firmamos nada simplemente, pues fue tratar de conciliar las cosas para que los medios ya dejaran de decir tanta cosa que no era cierta.

GUZMÁN: El 29 de marzo se hizo la marcha titulada “Respeto a la diversidad, no a la discriminación de la juventud". Era un día lindo, cálido... Varios emos, algunos acompañados de sus padres, otros solo de sus amigos, llegaron con carteles y gritaban consignas.

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVO)

REPORTERO: Al grito de tolerancia y respeto, 300 jóvenes de los llamados emos realizaron una marcha este fin de semana.

GUZMÁN: Todo esto nos puede parecer cómico ahora, pero Daniel Hernández, el periodista con el que hablamos antes, asistió a esa primera movilización y tiene una visión muy diferente.

HERNÁNDEZ: Como que me da mucho sentimiento, como los veía como “mira a estos chamacos como marchando por su derecho de ser”… que es algo muy básico y algo que todos podemos sentir y compartir.

GUZMÁN: El recorrido fue desde la Glorieta hasta el Chopo, aunque muchos tenían miedo de ser recibidos con violencia y ser expulsados otra vez. Luna Negra usó su influencia de rockstar respetada del Chopo para hablar con sus dirigentes:

GONZÁLEZ: Les dije: “¿Saben qué? El tianguis del Chopo se caracteriza por ser un espacio abierto a todo tipo de expresiones sobre todo todo lo que es llamada las tribus urbanas”.¿En qué se estaba convirtiendo el tianguis del Chopo? Si se supone que es un lugar abierto a todo tipo de expresiones, que defiende los derechos humanos, que defiende los derechos a la libre expresión.

GUZMÁN: Finalmente los convenció de dejarlos terminar allí la marcha. Era algo simbólico… terminar la marcha por la paz entre los grupos en el lugar donde ese hostigamiento había comenzado.

Cuando salieron de la Glorieta y empezaron el recorrido se dieron cuenta de que había una gran cantidad de policías resguardándolos. Era inusual. Los reportes dicen que eran 230 oficiales.

Al acercarse a la entrada del Chopo encontraron una tela convertida en un letrero que parecía haberse hecho con mucha prisa y poca pintura, pero el mensaje era lindo. Decía: “Bienvenidos al Chopo, emos”. Y otra un poco más grande en la que se leía: “El Chopo en favor de la cultura y la tolerancia”.

Pero en la entrada también había un grupo de anti-emos, no muy contentos con recibir una marcha de emos y menos con tantos policías. El ambiente empezó a volverse tenso. Y aunque uno de los organizadores del Chopo estaba hablando con un altavoz diciendo que “todos los tipos de personas son bienvenidos al lugar”, el conflicto se encendió una vez más.

Comenzaron los gritos de amenazas, de burlas…

Escuchen este grito: el que no brinque es emo.

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVOS)

ANTIEMOS: ¡El que no brinque es emo, el que no brinque es emo, el que no brinque es emo!

REPORTERO: Al llegar al también llamado crisol de subculturas, metaleros, punks, góticos y darks los recibieron con chiflidos, recordatorios familiares y hasta uno que otro botellazo.

GUZMÁN: Aunque pisaron por un momento la entrada de la tierra prometida, tuvieron que alejarse del Chopo para poder terminar el día tranquilos.

No fue lo que querían, pero tampoco dejó de ser una victoria. En los días siguientes, ya en abril, hubo varias reuniones entre autoridades, el consejo de la juventud de la Ciudad de México y grupos urbanos. Luna Negra y Darynkayna estuvieron presentes ayudando a explicar las dimensiones del problema y organizando estrategias para resolverlo. Como resultado se hizo la campaña “por la libertad de ser joven, vive y deja vivir”. La discriminación contra los emos se hizo un asunto oficial de Estado. Incluso la Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos publicó una investigación del conflicto.

GUZMÁN: Las cosas no se calmaron instantáneamente, se seguían reportando amenazas en diferentes zonas del país, pero los adolescentes ya no estaban enfrentando la situación solos.

Se abrieron carpetas de investigación para dar con los organizadores virtuales de las golpizas de marzo y se siguieron haciendo actividades para la campaña como conciertos, concursos, foros… Hasta que un día amanecimos sin ataques contra los emos, pero eso es porque ya no había emos a quién molestar.

En lo que pareció como un abrir y cerrar de ojos los emos se extinguieron. Ya no encontrabas a ninguno en la Glorieta, ni en los pasillos de mi escuela, ni en las plazas… ¿se cansaron del maltrato y renunciaron al estandarte emo?, ¿finalmente los antiemo lograron asustar a todos?

En realidad nuestra generación simplemente creció. Los emos más grandes entraron a la universidad y todos siguieron construyendo su identidad hacia otras direcciones. Daniel Hernández, que ya tenía bastante tiempo dándole seguimiento a los emos, también recuerda esa transición.

HERNÁNDEZ: Para mí siento que muchos estaban iniciando su camino a su eventual cultura con la que se iban a quedar.

GUZMÁN: Emos se hicieron punks, otros goths, otros hasta skaters o raperos… o qué sé yo… podcasteros…

HERNÁNDEZ: O hasta un hippie neoazteca. O salieron como personas queer.

GUZMÁN: Para muchos la etapa emo fue un terreno para poder explorar su identidad sin ser juzgados ni esconderse. En México, hasta la fecha, existe el estereotipo de que los hombres tienen que ser muy masculinos, fuertes, aparentemente sin sentimientos, rudos… Cualquiera que se saliera de esa línea podría ser etiquetado como gay.

Pero entre los emos nadie juzgaba la apariencia ni la vulnerabilidad del otro. Ese era precisamente el punto, tenían la libertad de ser. Los hombres emos también invertían tiempo en maquillarse, algo que era polémico.

HERNÁNDEZ: Por primera vez se veía, según yo, entre jóvenes ehm... chamacos, hombres, usar maquillaje de ojo. Y eso también como para algunos… este… mexicanos era algo como gay, ¿no? Era algo que un hombre o un niño no debe hacer.

GUZMÁN: Probablemente muchos punks y darks estaban genuinamente enojados porque sentían que los emos estaban plagiando su estilo… pero en el fondo, tal vez, gran parte de esos ataques, hostigamientos y bullying colectivo fue algo más simple, y más arraigado en la sociedad mexicana: la homofobia.

La tendencia emo arrasó y había muchos hombres que se sintieron amenazados por ello. Recuerden las palabras de Kristoff: “tendencia para niñitas”. O los insultos que les decían en la calle: “pinches emos putos…”, que en México es una manera muy despectiva de llamar a los gays.

Pero sin proponérselo y probablemente sin saberlo, los adolescentes emos cuestionaron el estatus quo del macho.

HERNÁNDEZ: Los emos estaban proponiendo una ruptura con las normas de género y las… y las normas que identificamos en una sociedad todavía muy machista como la es de México, este… de algo no de varones o algo así eso también fue un punto de conflicto o de violencia o de un intento de opresión.

GUZMÁN: Y aunque el emo nunca se convirtió en una subcultura establecida, “oficial”, como las demás... por ese simple hecho de cuestionar esta masculinidad, ya son legendarios.

ALARCÓN: Daniel Hernández escribió sobre los emos y punks en su libro Down & Delirious in Mexico City, que recopila esta y otras historias increíbles de la Ciudad de México. Highly recommended. Tenemos un link en nuestra página web. Actualmente cubre cultura en el LA Times.

El Mosco y Bake, o sea Ollín y Alejandro, crecieron y dejaron atrás el emo. Formaron parte de una banda y actualmente se dedican a sus trabajos ya su vida adulta.

Darynkayna y Luna Negra no han podido regresar al Chopo por la pandemia. Pero siguen siendo parte de la escena alternativa de la Ciudad de México de manera virtual.

Un agradecimiento especial para Roger Vela y Pablo Merodio. También para todos los ex emos, punks y goths que consultamos para este episodio, gracias por su ayuda.

Esta historia fue producida por Fernanda Guzmán. Es asistente de producción de Radio Ambulante y vive en Ciudad de México.

Este episodio fue editado por Camila Segura, Nicolás Alonso, Luis Fernando Vargas y por mí. Desirée Yépez hizo el fact-checking. El diseño de sonido es de Andrés Azpiri y Rémy Lozano con música original de Rémy.

El resto del equipo de Radio Ambulante incluye a Paola Alean, Lisette Arévalo, Aneris Casassus, Xochitl Fabián, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Jorge Ramis, Laura Rojas Aponte, Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo y Elsa Liliana Ulloa.

Emilia Erbetta is our editorial intern.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante es un podcast de Radio Ambulante Estudios, se produce y se mezcla en el programa Hindenburg PRO.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I am Daniel Alarcon. Thanks for listening.

one

Copyright © 2021 NPR.All rights reserved.Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR's programming is the audio record.