Gregorio Luri: "A stable family is a psychological bar

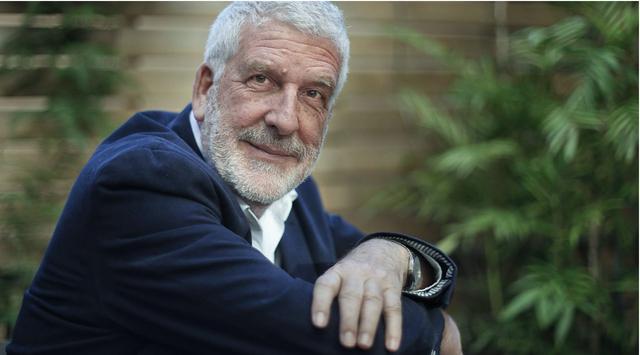

Gregorio Luri (Azagra –Navarra–, 1955) is not a marriage mediator or couple psychologist. In case he caught the headline and was looking for a speech therapist to sit in his living room. But he is a Spanish philosopher, educator and essayist with a high public presence among today's columns, yesterday's reflections and forever books that would go very well in an armchair at home or in a corner of a bar where there is not much ambient noise.

Public opinion grants him the degree of expert in Education, because he has a degree in the subject, because he has been a primary school teacher, a high school teacher and a university professor, and, above all, because he has thought a lot about everything he He himself has lived at all levels of that pillar of the Welfare State where they teach us to be better people among black holes.

He is a humanist, analyst, reflective thinker, natural, simple, realistic, optimistic. Veteran in spreading the positive, he is accustomed to avoiding the temptation to wield the hammer of heretics, whipping up his own orthodoxy and willing to build something solid on foundations that are not liquid post-truths designed in the ideological metaverse.

He is optimistic, among other things, because almost every day, at about 10:30, he goes out to soak up the Mediterranean sun when it shines over El Masnou, between Barcelona and Mataró. From one of his squares, he answers me today while looking at infinity against the light, as can be sensed in the intonation of his answers. At his side, a book. In front, the horizon of the flowing sea, but in Democritus mode: spraying illusions without hints of disappointment with humanity. He apostrophes: “Today, more than ever, it is urgent to project optimism. Whatever happens, let hope be the last word that comes out of our mouths."

Wise gray hair. Luri is the author of The sentimental jam, The school is not an amusement park, In praise of sensibly imperfect families, The moral duty to be intelligent or The conservative imagination. suggestive Provocative of own ideas. An honest independent amid the cracklingly uniform magma of the factions. A philosopher, an educator, a father, a grandfather.

— The writer Carlos Zanón says in El Mundo that “being a man implies a certain emotional handicap”.

— It is obvious that we are emotionally handicapped. We all need each other, we all seek joyful work and secure love. We are all after compensations for our frustrations. Since today we live largely on illusions, we have created the image of a mentally healthy human being that would make Freud laugh out loud, because there is no such thing as a healthy soul.

— Is this “certain handicap” only masculine?

— Affects all human beings. We are always below what we consider possible and, furthermore, we are made of time, and for this reason we have a chronically unstable relationship with limits. If we review the history of humanity, we will see that there has always been an attempt to exceed limits and that is the clearest proof of our psychic limitations. Rousseau said that "man is a sick animal", and there is something of that.

— Within the tsunami of emotivism that you speak of in The Sentimental Jam, how do you synthesize the paradigm of what the media calls “new masculinity”?

— I can't quite digest that kind of nonsense. When we review history, we observe that every present conjugates narcissism, a certain veneration of a mythical past and a desirable future at the same time. The "new masculinity" is a rhetorical expression, but what I see is something else.

—What?

— I see a predominance of the ephebe as a cultural figure. When contemplating the men and women of our time, I observe a drift towards the ephebe. This is not another masculinity, but a new assessment of adolescence. It is as if we were increasingly resisting the duty of being adults.

— More than aspiring to maturity, have we entrenched ourselves in adolescence?

— Yes. The adolescent has become a venerable cultural figure. Narcissism, which was considered a typical element of adolescence, has already disappeared as a psychological disorder in psychiatry manuals, because something that is universal cannot be considered a disorder. When I studied Pedagogy or Evolutionary Psychology, the limits between childhood, puberty, adolescence, youth were well established... Today, when does adolescence begin? We see ten-year-olds with adolescent gestures, attitudes, clothes, hairstyles, and expressions, and we see fifty-year-olds.

— In the liquid society of which Bauman speaks…

— … I had the opportunity to meet him. It must be very clear that Bauman is not a prophet of the liquid society, but rather its critic and its enemy. He himself told me that he lived with his wife until the end and when she died, he got married immediately, because his motto was: “against liquid societies, solid loves”.

— In that liquid society of which Bauman warns and which exhibits its shame, what the words call “fluid gender” has been consolidated. More uncertainty in this global context of instability, in this case in our identity schemes. Heraclitus is more alive than ever in the midst of this world...

— Heraclitus is the philosopher who cries, compared to Democritus, who is the philosopher who laughs. The continuous movement and the eternal fluidity lead to melancholy.

— In this prevailing context, it is understood that there are people who are emotionally lost, without attachments and without references. I don't know if this is a jam, a stew, an empanada or an anthropological and social trompe l'oeil.

— [Laughs] I think we should spend as little time as possible criticizing what we don't understand and devote that effort to naturally affirming what we believe and who we are. We will not be judged by the eloquence of the speeches we make, but by the ethical and moral example that we offer. If we believe that solid love is a fundamental good, we will show it naturally. If we think that a stable family, with all its imperfections, is a psychological bargain, let's tell it. If we see that a mind with well-defined concepts allows us to move through the world with more clarity than if it runs between ambiguous and indefinite concepts, we are going to normalize that firm and untrammeled thought. It is urgent to abandon both the scandal and the permanent criticism of what we do not like, to simply affirm ourselves in what we are and in what we like.

— I have the impression that the metaverse already existed before Zuckerberg: there is a life of concepts where we do pirouettes with words and expressions, and then there is the reality of every day, in which everyone knows exactly what is important What is in your life solid love, family, education, faith...

— What have been the great lessons of the pandemic? For me, the first has been that when large structures falter, the family ends up being the essential resource, something we see in all moments of crisis. Where the State does not arrive, the family goes, which is always with its doors open. We have also learned that, as much as we consider that death has something pornographic that must be hidden and avoided, it is there, and life, beauty and love only have meaning when we know that everything we love and everything we admire is there. touched by death.

— Politics has put at the top demagogic campaigns that disturb and generate added social uncertainties to those we personally experience. More than lending us a hand, it vomits new anxieties at us every day. How do we prevent ideology crafted by people we don't care about from entangling our biographies?

— Faced with the triumph of historicist ideologies that tell us that everything is socially constructed and, consequently, we can design everything as we please, it is essential to firmly defend the values of the normal citizen and his vital system. As Chesterton said: laughter, marriage and beer. I don't know if the president of the Community of Madrid realizes that she has hit the target defending cane as a value. Having a beer with friends is a fundamental political act. The defense of the everyday values of normal people is essential. The sentimental jam is, deep down, the result of seeing the world with the teary eyes of Heraclitus, because those tears blur the real look and prevent us from seeing the joy and celebration of one's own existence. When you do politics or ethics solely from pain or tears, you are reducing the complexity of reality. Pain is neither an ethical nor a philosophical category, but essentially a religious one.

— It is clear that everyone must look for their own life preservers and, in any case, propose them to our peers to avoid shipwreck. Can the humanities be a certain grip?

— I am not a fetishist either for books or for the humanities. There are people out there who praise the book without measure, perhaps because they have read little, because there are also bad books, dangerous books and books that make people suffer. I would not recommend Plato's Parmenides or Hegel's The Phenomenology of Spirit to anyone, even if I have had to face them as a philosopher. They are books that present you with struggles in which you frequently fail. What I think we need are humanists and readers who show us the positive example of what the humanities can give of themselves. Humanism does not solve anything for us. Humanism complicates our lives. Humanism, if it is useful for anything, is to show us the complexity of life.

—Are public virtues handy life preservers?

—We could make a wonderful speech about public virtues, but it would be a tad hypocritical. Public virtues are always in short supply, but that's part of real life. When our mouths are filled with public virtues, deep down we are defending a quixotic morality, imbued with great ideals and romantic nobility. The morality we need is that of Sancho. For me he is the true hero of Don Quixote.

—Why?

— Because he doesn't follow an ideal, but a person he knows so well that he doesn't miss any of his flaws.

— What is the fundamental public virtue?

— The ability to commit to noble causes knowing that they are imperfect, because no reality in which human beings participate is perfect, not even the Church. If we were clear about this, we would find in this commitment a vaccine against deep disappointment and alienated enthusiasm. It is the political virtue of prudence, essential for Aristotle.

— Being realistic is a gift.

—Reality is what we have to save to save ourselves. As Ortega y Gasset said, “I am myself and my circumstances”. In that sentence, which has been interpreted in many incorrect ways, the key is the link, the "and". I am that "and". Pretending to criticize my circumstances to save myself is an unwise project.

— Philosophy is increasingly present in the media…

— … I'm not sure. Philosophy is always a very personal effort. It is more a search for something than the enjoyment of what has been found. At the moment in which the philosopher believes things definitively, he becomes a sophist. Ideas circulate in the media, and sometimes very interesting ideas, but that does not mean that Philosophy is there. Philosophy has something antipolitical and the characteristic of politics is fallacy, said with all dignity.

— I see more philosophers with a presence in public opinion, and I don't know if it is precisely because society needs to hear realism in the midst of so much extreme, so much mirage, so much fake, so much conspiracy, so much subjectivity, so much ideological proselytism and so much hoax

— In Spain there are many ideologues, but, although there are many Philosophy professors, I can't find any philosophers. Hopefully I'm wrong.

— You wrote School is not an amusement park. Taking responsibility for academic training for granted, are Spanish schools healthy places for the affective and emotional training of new generations?

Schools have fallen into a very curious trap, believing that it is possible to educate affectively and affectively without parallel intellectual and moral training. It is impossible to clarify emotionally with oneself when linguistic poverty is rampant. The care of the soul cannot do without rigorous knowledge, because they provide experiences of order. If we suppress those experiences of order to try to create emotional stability, we are fooling the student and ourselves. On the other hand, I doubt very much that emotions can organize themselves without the help of a non-emotional principle. More important than talking about emotions is knowing what kind of people we aspire to be. The emotions that a surgeon needs are not the same as those that a romantic poet or a miner requires. The exacerbation of the emotional that ignores the type of person who serves as a model is one of the reasons for the sentimental jam.

— What are the keys so that a person's education is not a fraud or a project doomed to failure?

— Freud said that there are three things we don't know how to do: govern well, preserve pristine health, and educate, because education always implies assuming the reins of your own life in the face of an indefinite future. We all have wounds and we are fragile. One of the conditions of a well-educated person should be the knowledge of his vulnerability and the understanding that he will never be well-educated enough. Today we tend to see education and the school from a psychological point of view, worrying about the well-being of the student, their skills, etc., and we forget something that has been essential in the school, especially in the public one: the republican dimension of education, in its etymological sense. We are citizens with other citizens. As the existentialists said, I am a being with. This must be educated, because the predominance of the psychological and the economic is eroding one of the basic dimensions of the human being: co-belonging. There is no single value that defines a well-educated person, because being a person is a very broad front. The important thing is to have the resources to manage all facets.

—Is the empire of relativism over?

— No. Relativism is a constant in European culture that began with the sophists of Athens. Removing it would be absurd. The important thing is to maintain a position in front of him. In European culture there are relativistic and nihilistic components that are part of its essence. Lev Shestov is the first to theorize something that Donoso had raised: that our culture is a strange mix between Jerusalem and Athens, impossible to harmonize and, at the same time, impossible to separate. Jerusalem invites us to a relationship with reality that hinges on faith, and Athens asks us for a relationship with reality that excludes faith and is purely rational. We cannot live solely by faith, nor can we live solely by reason.

— This mix between relativism and nihilism leads me to an idea that you frequently highlight: that the barbarians who conquer us are no longer the others, but ourselves.

— Now that is a spectacularly striking phenomenon very typical of Europe. Until recently we could divide the European political map between progressives and conservatives, but in recent decades, progressivism has become fearful of the future. In fact, we are living in a kind of permanent locution of the apocalypse. Our children are being educated in schools with the fear of the future as a background. Oh, oh, oh, what awaits you! The apocalypse is a concept that seemed completely outdated and the anxiety of young people for the future is already a syndrome that collapses consultations. Educating in fear in the future is disturbing, because if we lose our serenity, we lose the possibility of finding answers to real problems. This relativism, this historicism and this nihilism that are part of the current social context reflect that man has tired of himself.

— And does this preventative apocalypse that spreads in schools, that monopolizes the media and that paints public discourse black with a vaccine?

— The real apocalypse is despair in the face of the apocalypse. Among the forgotten virtues or emotions, there is one that for me is the most necessary: serenity, because it allows us to develop a broad perspective on the environment. Is there a vaccine? It seems to me essential to trust the human being, but we must be aware that we are in a new situation. The image of man turned into the authentic virus of nature is terrible and very harmful. I even see that it spreads in some ecclesial sectors with extraordinary frivolity. Talking about the king of creation is not an insult to ecology. If we get out of this it will be because man assumes the weight of everything. Perhaps the most extraordinary thing about human beings is that we are capable of worrying about the whole. We are a minuscule part of the cosmos that cares about the absolute totality of things. This capacity is one of the reasons for the permanent neurosis of men and also one of the reasons for hope.

Alvaro Sánchez León @asanleo