How America Struggled To Become An Empire And Then Tried To Hide It

On October 25, 2018, a Category 5 storm struck the United States. With maximum sustained winds of 241.4 kilometers per hour, it was the most powerful anywhere on earth that year, and the strongest in the country's history, since 1935. It tore roofs off homes and severely damaged the power grid. .

Despite the damage, the superstorm barely made headlines. It received less than 1% of the television coverage devoted to Hurricane Florence, which had struck North Carolina earlier that year. It was, wrote Anita Hofschneider of the Columbia Journalism Review, "the super typhoon the American media forgot about."

That storm garnered little attention because of where it struck. Typhoon Yutu swept through Saipan and Tinian in the Northern Mariana Islands in the western Pacific Ocean. These islands are part of the US, and people born there are US citizens. But few in the country seem to know.

“I'm afraid most Americans don't know we have overseas territory,” says Phil Klotzbach, a hurricane expert at Colorado State University. Weather, like war, has a way of teaching geography lessons. In fact, the US has several overseas territories, including Puerto Rico, Guam, and American Samoa. And he had more in the past.

On the eve of its entry into World War II, the US empire (which included the Philippines as well as the territories of Hawaii and Alaska nearly two decades before the latter two became states in 1959) had about 19 million settlers.

Back then, if you lived in the US (the entire country, not just the North American mainland), you were more likely to be a settler than an immigrant. In fact, there were more settlers than African Americans. Historians today are grappling with these facts. More and more often they tell the story of the United States as that of an empire.

The expansion of an empire

That story begins from the first day of the nation. “The name of this Confederation shall be the United States of America,” according to John Dickinson's 1776 draft Articles of Confederation, capturing the heady wave of political possibilities of those early days.

The country would be a union rather than an empire, made up of states rather than a homeland and colonies. Except the name wasn't exact. When Britain ratified the Treaty of Paris in 1784, which gave the country sovereignty, it was not a union of states. The government had taken the westernmost lands of states like Virginia and Massachusetts and placed them under federal supervision.

So the US was a collection of states and territories, and has been ever since. For the first seven decades or so of their history, those territories adjoined states and were expected to join them. But just three years after completing its final western annexation in 1854 (obtaining a portion of Mexico known as the Gadsden Purchase), the US embarked on a new phase of expansion abroad.

He began by claiming dozens of uninhabited islands in the Caribbean and Pacific, sources of guano, an essential fertilizer for nitrogen-parched farms. After a deal with Russia he incorporated Alaska. A pivotal war with Spain in 1898 brought the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam into the country. And the non-Spanish lands of Hawaii and Samoa were annexed at about the same time.

By 1900, the Overseas Territories covered an area as large as the entire United States at its founding, and had a population more than twice that of the original territory.

The use of the word “America”

Impressed by the country's expansion abroad, cartographers offered new maps showing the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and other territories alongside states. The writers, convinced that the overseas empire marked a new era, reconsidered the name of the country.

Technically, its name was what Dickinson had given it (“United States of America”), but in the 19th century it had been more commonly called “United States,” “The Union,” or “The Republic” for short. . However, after the great imperial land rush, these names no longer fit so well. Whatever the country was, it was not a union, it was not a republic, and it was not limited to the states.

Various names were proposed: “Imperial America,” the “Great Republic,” and, a phrase that appeared in the titles of seven books published in the decade after 1898, “Great America.” Dissatisfaction with “United States of America” led to a more lasting verbal change. Before 1898, although its people called themselves "American," it was unusual to call the country "United States of America." One could travel more than 8,000 kilometers and read 100 newspapers before coming across that name, a British writer observed.

“United States of America” did not appear in any of the patriotic songs (such as “Yankee doodle”, “The battle hymn of the republic”, “Hail, Columbia”, “The starts and stripes forever”, “The star -spangled banner”). A search of speeches by presidents from the founding to 1898 returns just 11 unambiguous references to the country as "United States of America," about one per decade.

After 1898, however, things changed rapidly. Theodore Roosevelt, the first president to assume the presidency after the war against Spain, used the word "America" in his first annual address and frequently thereafter. The name was looser, expansive, and implied nothing about the country being a union of states.

Every president since has used the word “America” freely. And new anthems emerged with titles like “America the beautiful” and “God Bless America.”

How to Make Stir-Fry Instant Noodle With Beef: If you don't have time and in a hurry to cook. Try stir-fry instant... http://bit.ly/d5OqeS

— Katie Blake Fri Oct 15 02:52:13 +0000 2010

A Hidden Empire

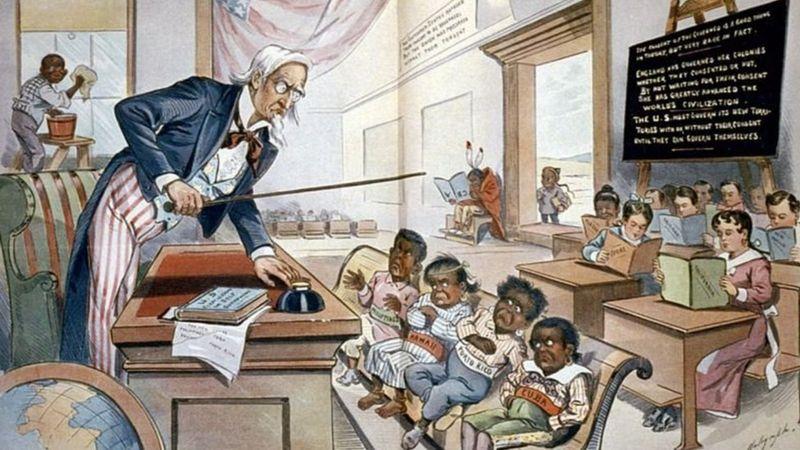

In the years after 1898, it was obvious that the US was an empire. Their maps showed the colonies, and powerful men in Washington openly vociferated their imperial ambitions. But then something strange happened. Perhaps due to the exhaustion of violence in the Philippines, or due to the persistent vision of the country as a republic, the powerful began to ignore the colonies.

Without giving them up, the US simply talked less about them, sort of sweeping them under the rug. By the 1910s, the colonies had largely disappeared from the maps and were no longer called as such. That word, a federal official warned in 1914, "must not be used to express the relationship that exists between our government and its dependent peoples."

This cognitive dissonance around empire, it should be said, was rather unusual. UK was not confused about whether or not it had colonies. He honored them annually on May 24, Empire Day, which was celebrated in schools for decades and became an official holiday in 1916.

As it happens, the US had its own patriotic holiday, one that also started in schools before it received federal recognition in 1916. The US version was called Flag Day, and was designed to encourage citizens to come together "in a united demonstration of their feelings as a nation," as President Woodrow Wilson put it in 1916.

There was no holiday for the empire. The writers said little about the colonies. The most famous literary engagement with them was probably "Coming of age in Samoa," a widely read 1928 ethnography written by anthropologist Margaret Mead.

But Mead wrote about Samoa the region, not American Samoa, the colony where she had lived. And she completely avoided mentioning colonies, territories, and empires. It is entirely possible to read Mead's book without realizing that the “brown Polynesian people” she describes as being on an “island in the South Sea” are, like her, American citizens.

In 1930, a representative year, the New York Times published more articles on Poland than on the Philippines. More about Albania than about Alaska. It published nearly three times as many articles on the UK's largest territory, India, as on all US territories combined; territories that were home to more than 10% of the US population

This lack of attention to the colonies mattered. It mattered especially in the 1930s, when Japan's imperial ambitions in Asia became clear. A quick glance at the map showed Guam, the Philippines, Alaska, American Samoa, and Hawaii as potential targets. In fact, Japan eventually attacked all of them.

But polls showed little public interest in sending the US military to defend those places, and military strategists did little to strengthen it. As a result, the meager defenses in the Pacific territories proved incapable of repelling Japan's first attack when it finally arrived in December 1941.

That attack is generally remembered in the US simply as an attack on the Pearl Harbor naval base in Hawaii. However, within hours, Japan also attacked the American territories of Wake Island, Guam, and the Philippines, the British colonies of Malaya, and Hong Kong; and the independent kingdom of Thailand.

Some attacks were launched on December 7 and others on December 8, but only because Japan's maneuver crossed the International Date Line. The event, known in the US as "Pearl Harbor", was in fact a near-simultaneous attack on several Allied possessions in the Pacific. The port was the first American objective hit. But it was clearly not the place where the Japanese did the most damage.

Official US Army history calls the attack on the Philippines equally damaging. Furthermore, while the attack on Pearl Harbor was just that, a single attack that was never repeated, the raid on the Philippines was followed by more assaults, then invasion and conquest.

The Philippines, Guam, Wake Island, and the western tip of Alaska, whose populations numbered more than 16 million US citizens, fell to the Japanese. The US eventually regained its lost Pacific territories, but at a cost that is rarely acknowledged. He bombarded all the important structures of Agaña (now Hagåtña), the capital of Guam, in his fight to reconquer the island.

Manila, the capital of the Philippines, was similarly decimated, as were many other Philippine urban centers. "We leveled entire cities with our bombs and shells," the Philippine high commissioner recounted. In the end, he said: “there was nothing left”. It is estimated that more than 1.5 million people in the Philippines died during World War II. It was easily the bloodiest event to ever take place on American soil, more than twice as deadly as the Civil War.

The war in the Philippines is not part of the national memory in the U.S. The National Mall in Washington D.C. it has no sanctuary for the dead of those islands. The carnage was, like Typhoon Yutu, something that happened "there," of limited relevance in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles.

Empire is worth thinking about though. The Philippines is no longer a US colony, having gained independence in 1946, and Hawaii and Alaska are now states. But the US still has five inhabited overseas territories: Puerto Rico, American Samoa, the Virgin Islands, Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands.

Some four million people live in them, four million people who cannot vote in presidential elections, are not protected by the constitution, and have no role in making federal laws.

This disenfranchisement is important. In 2017, Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico, knocking out power for months. Thousands died as a result of the storm, but it wasn't the weather itself that killed them directly. It was longstanding neglect, followed by a lack of federal aid after the hurricane struck.

“Recognize that Puerto Ricans are United States citizens,” was the desperate plea of the island's governor, Ricardo Rosselló. However, a survey of US residents conducted after the hurricane showed that only a slim majority, and barely a third of adults under the age of 30, were aware of that fact.

One wonders if those numbers will be higher when the next storm hits.