"Stay as Cagancho in Almagro" |Tomelloso's voice

The first times I heard people say “He stayed like Cagancho in Almagro” I wondered: Was he a real character, or an imaginary one? If it was a real character, who was Cagancho? A comedy actor who performed in the famous Corral in the city of La Mancha? A bullfighter who fought in his bullring? When he lived? Where does that phrase come from? How did it become popular and why?

It certainly does not refer to the mythical bullfight horse of that name that brought so much glory to its owner, Pablo de Hermoso de Mendoza, at the end of the last century.

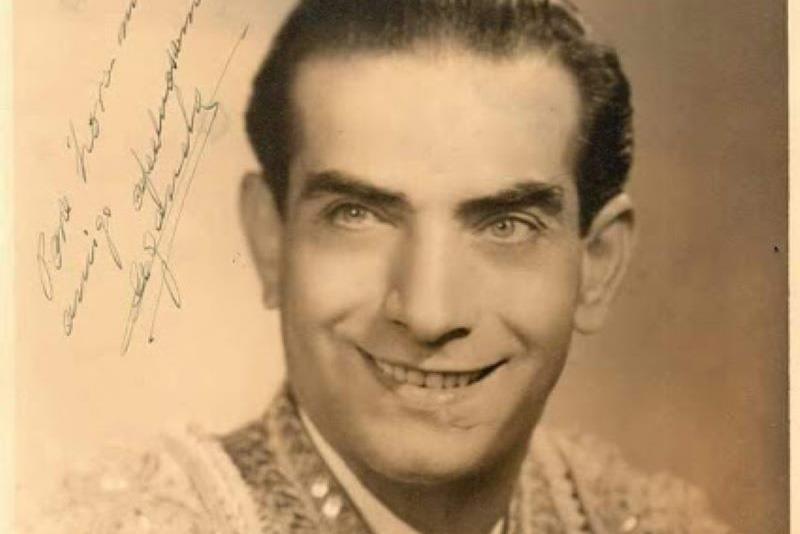

I discovered that Cagancho was a real character. It was the family nickname of Joaquín Rodríguez, namesake of the right-hander “Costillares”, but with a second surname Ortega, born in Seville, in the Triana neighborhood, on February 17, 1903. Gypsy, son of a cigarette maker and a blacksmith and grandson of a cantaor of flamingo.

Regarding the nickname, there have been many and varied versions. The malodorous ones from the Catalan bullfighting press, (among other writings: "Because, come on, frankly, / that impertinent nickname / is an offense to smell, / because of what is new and smelly, / it does not suit a pageantry artist with dignity." ). The ones that their blacksmith ancestors made hooks for the Romans: “Ca hook for two reales”. The one that sold clothes in markets: “A real cagancho”. And the most widespread, most amiable and lyrical, that was performed for his grandfather the cantaor, in his youth, because he sang like a bird from Huelva, the “cagancho”, which sings wonderfully.

Cousin of Francisco Vega de los Reyes, Curro Puya, the first “Gypsy from Triana”, the queen in 1931, dressed in ash and gold, killed the Fandanguero bull in Madrid.

That Cagancho, a gypsy with green eyes, dedicated himself to the art of bullfighting, debuting in public in 1923, in San Fernando (Cádiz), with steers from Bohórquez. A year later, on July 25, 1924, he made the official presentation before his countrymen at the Real Maestranza de Sevilla, during a modest nocturnal gathering. In Las Ventas he did it on August 5, 1926, with steers belonging to the Marquis of Villamarta, reaping resounding success. He took the alternative on April 17, 1927, in the Plaza de Murcia, his godfather being Rafael el Gallo with the "Orejillo" bull, from the Carmen de Federico ranch, already inaugurating the scandal.

Then it was written: “Cagancho is already a killer, / that the Rooster gave him a sign, / and he already gives in the round / the cañí, as a speaker, / the rally better than that one. / What will become of this gypsy?/ Will it be an abyss, a peak, or a plain?/ Nobody knows for sure; / today it is an arcane, / rather: a riddle.”

He confirmed the alternative in Madrid, on June 22 of that year, having Valencia II as godfather and Lalanda as witness, with the bull "Naranjo", owned by María Montalvo. In that season he fought 46 bullfights in Spain with unequal fortune and 10 in Mexico. On May 7, 1931, in the arena of Villa y Corte, nine years after Granero died there, he fell seriously injured by a bull owned by Alipio Pérez-Tabernero, which inflicted two gorings on him, one in each thigh, unable to to do the paseíllo again until August 2, when he reappeared in Cádiz. In the 1934 season, on October 21, he participated in the official inauguration bullfight of Las Ventas (Madrid), alternating with Belmonte and Lalanda, obtaining a great victory and coming out on his shoulders, according to what Gregorio Corrochano tells us in his ABC chronicle on October 23. . In 1935 he fought 30 bullfights in Spain, fighting others in America, interrupting the war on his bullfighting path.

And at the Tomelloso festivities in September 1933, as this newspaper informs us (March 25, 2021) Ángel Martín-Fontecha, on the 12th, would fight our Cagancho, hand in hand, with Manolo Bienvenida, cattle from Domecq , offering a show, a synthesis of his style: "two announcements in his first bull, [and] he finished his performance to ovations and applause". By our account we have found that he returned to fight at the Tomellosera fair of 1935, on September 11, bulls of Santa Coloma, replacing El Estudiante, alternating with Armillita and Curro Caro. In the first, despite carrying out a "courageous task", he reaped whistles by killing with a lunge and three outrages, making up for himself in the fourth which he "adorned" with his mulete, obtaining an ovation from the ear, although it would be eclipsed by the great task of Curro Caro the third that he saw rewarded with two ears, tail and turns. (La Libertad - Year XVII Number 4820 - 1935 September 12 (09/12/1935), p. 4.)

Cagancho became one of the idols of the Mexican fans where he had lived since 1953. There, he managed to cut eight tails between the years 1932 and 1936. In the Plaza del Toreo in Mexico City, on December 27, 1931, in a bullfight for the benefit of the Press Association, he fought with Vicente Barrera, Fermín Espinosa, Armillita Chico and Alberto Balderas, bulls from Zotoluca. The "Medal of Art" and the "Medal of Valor" were awarded. In the fifth bull he made the public go crazy with a task so sublime and prodigal in beauties that, after puncturing once and leaving a perfectly executed toss, he produced delirium; the ears and the tail were awarded the "Medal of Art" by unanimous acclamation. The one of Valor was for Vicente Barrera.

Santainés recounts that he saw him fight in the Monumental de Barcelona on June 7, 1942, where he performed a masterful performance but that a spectator commented: "What a good bull this bullfighter has touched!", to which Pepe Berard, a great friend of Cagancho replied: "What a good bullfighter that bull has had!"

He starred in several films: Gypsy Passion (Díaz Morales, 1945), Los amores de un torero (1945), both with Carmen Amaya and Ángel Garasa, and work in Santos el magnífico (Budd Boetticher, 1955) alongside Antoni Quin.

He returned to Spain, almost secretly, in the 1960s. He said he did not want all the women who loved him to see him as old.

In Mexico, once he retired, he suffered financial difficulties. The President of the Republic, López Mateos, appointed him a Government Counselor to be able to pay him a salary at the end of the month. At a meeting, the Minister of Economy, jealous of the unfavorable treatment of the bullfighter, asked him in public: "Maestro, do you know English?", to which Cagancho replied calmly: "Not even God allows it."

He died in the capital of Mexico on January 1, 1984, at the age of 81, a victim of lung cancer, having alternated with all the figures of the different bullfighting eras that followed one another during his long professional life, from Belmonte to Aparicio and Litri, whom gave the alternative.

Like other gypsy bullfighters (Rafael Gómez "El Gallo", famous for his scarecrows, Gitanillo de Triana, CurroRomero, Rafael de Paula), he was capable of the highest and the lowest in the arenas. Superstition in a trade like bullfighting in which life is at stake has greatly influenced these artistic bullfighters capable of imprinting on their trade the magic of their race, the irrational feeling and emotion, the most exquisite, the most brilliant and the most heroic. , in front of the crudest, the most clumsy and the most cowardly.

Capable, sometimes, of interpreting, as Bergamín wrote, the most marvelous “silent music, his music for the eyes” or of provoking, at other times, the most strident whistles and the loudest and most horrifying fights, according to the sensations that the bull transmitted to them or believed to perceive. Simply a "looked at me wrong" was enough to sow panic in them.

“With great ease he went from the sublimation of an exquisite art to the most grotesque failure, from the most unsuspected peaks to the deepest abyss” Antonio Santainés Cirés wrote of him.

We already know who Cagancho was, but what does the phrase mean and where does it come from?

“To remain like Cagancho in Almagro” is to look fatal in the public eye because that is how Cagancho was left in August 1927, on the 25th, in the Plaza de Almagro. He formed a shortlist with Antonio Márquez and Manuel del Pozo, Rayito. They were the bulls from the Pérez Tabernero ranch. As told by J. de la Morena, in the third, first of his own, came out to make a quite; the bull disarmed him, making the cape fly and the teacher ran towards the barrier. That's where the fight started. With the crutch he was distant and cowardly. As soon as the bull looked at him, he would run. He pricked the bull in the neck, and then in the arm, he pricked nine more times and went on to go crazy five. His second bull, the sixth in the afternoon, in the luck of rods, killed several horses. In the last third, they say that he took out an enormous crutch and began to fight with the beak of the cloth. In one of the passes, he struck him in the belly with his sword, and then another. The bull gave him a bad look, so the bullfighter threw away the tackle and repeated the fate of the third bull: running towards the barrier. And, once inside, as the bull approached him, he pricked him again. The third warning sounded while Cagancho continued trying to kill the animal without leaving the barrier. He did it by pricking him on the sides, on the arms, anywhere. Those of the subordinates who dared to jump into the arena did so with their swords under their cloaks, they approached the bull and also treacherously pricked it anywhere. The bull was alive, and the ring was already beginning to fill with spectators who had jumped into the arena. People began to chase Cagancho, who tried, sword in hand, to leave the bullring. It is said that a spectator grabbed him by the neck and, throwing him in the opposite direction, yelled at him: - To the bull, damn it! Coward!- And there was Cagancho, in the middle of a ring full of people who surrounded him to give him a beating; meanwhile, the live bull, bleeding from its thousand wounds, loosed bolts, taking the people ahead. Then he charged a cavalry detachment that was there reinforcing the Civil Guard. On horseback they managed to clear the ring. Eight civil guards surrounded Cagancho and took him out of the square, among a shower of all kinds of objects.

The failure of Cagancho in Almagro was, it was said, the biggest row ever occurred in a public spectacle in Spain. The march of the right-hander was followed by disturbances in the square and in the surroundings, which led to the forces of order charging on horseback.

Almagro, that afternoon, was such a strong pitched battle that it remained in the memory of the Spaniards, for whom "remaining like Cagancho in Almagro" became the symbol of absolute failure. Cagancho, still dressed in lights, sheltered in the assembly hall of the Almagro City Hall, guarded by the civil guard so that the personnel who were in the street would not kill him, it is said that he commented: “That's life. I wanted to look good, but what can't, can't.” One of his subordinates complained to the civil guard. – “Does it seem logical to you that they want to put him in jail [for Cagancho] for not having killed a bull and they want to do the same to us for killing him?

In enough detail, but with moderation, the anonymous chronicler of Diario ABC on August 26, 1927 recounted that in the third, “Colorao, bragao and collected with horns,….Among a row, he gives a flat tire, blatantly throwing himself away; another equal; another, (Monumental anger.) Another ugly quartering; other. (Great scandal.) Another stab wound; five pithing attempts by Cagancho. (Enormous anger.) Guerrilla stabs the bull the first time.”

And in the sixth, “big and with good defenses” he writes: “On the way out he sows panic among the bullfighters. Cagancho flees, and the public protests loudly... The work of this incomprehensible bullfighter is a lamentable spectacle. He flees before the bull, punctures however he can and wherever he can, piercing the bug on all sides, gripped at all times by an indescribable panic. The anger is deafening. A warning sounds and Cagancho, fed up with DJing, takes the barrier and tries to leave. The public apostrophizes him. Rayito goes crazy, and Cagancho is taken to jail amid unspeakable yelling. Nothing could be more shameful."

And the following day, he reported that they were released from prison after paying the fines of 500 and 250 pesetas that the Governor imposed on him and his gang, since “To avoid harm to the company in Almería, the capital where Gagancho fights today , the governor did not want them to be detained, otherwise they would have been there longer" And he concluded: "No other scandal greater than that of yesterday is remembered, and if Cagancho is not protected by the Civil Guard, the crowd, enraged, due to the unprecedented freshness from the right-handed, I would have lynched him. However, Cagancho received some blows.”

The Almagro episode was neither unique nor coincidental.

Already on the afternoon that he took the alternative, on April 17, 1927, in the Plaza de Murcia, he had inaugurated the scandal. The review the day after in the newspaper “Levante Agrario”, among other things, said that “Cagancho, in white and gold, with bell rings, showed us that he is not a bullfighter, nor has value, nor does he know how to fight. He did nothing. In the removes ... rebuked by the public. In the second bull he gave a superior average speed, but nothing more. At 5:12 (official time) he was made a bullfighter. The bull was called “Orejillo”, he was a black bragao and a hosiery maker, and he bore the number 205. The neophyte begins with precautions with help from below, moved, without sending anything (whistles) more passes, fleeing in some, and half a neck throwing himself out ( anger) hits the second attempt, and there is a good pita ”. Lalidia del sixth bull [which the chronicler describes as “sweet pear”] was a continuous whistle to Cagancho, with shouts of Let him go! Let him go! In the kicks he would stampede to the barrier, and so things, touch to kill and debacle!, low passes two meters away, losing several times the crutch and herding the barrier. If this is the day of your alternative!, what will it be later on? the karaba! The bull was ideal, charging every time he moved his crutch, and entering frankly, without goring, and the sword running away, running away, running away... A puncture in the neck coming out of stampede, and half a neck. Time passes. More passes. Two pithing attempts. Time continues to pass, and the presidency is sleeping, after 13 minutes they give him the first warning (a big rant) two more attempts and he is right.

He leaves the square guarded by the police amid a deafening anger, the right-hander listening to all the phrases that are said in these cases. In a car the bullfighter is guarded with the secret, and surrounded by security guards. He does not dare to take the train at the station and goes by car, protected, to the Sewer station, where he takes the mail.

And in Caravaca, (Murcia), the following May 1, before a disastrous performance, throwing the two bulls into the corral, again, he had to leave protected by the public force.

He had left a bull alive the afternoon of his doctorate in Seville and both in the following bullfight, although he achieved extraordinary success in Toledo on May 8, 1927. On that occasion, he performed an “unspeakable” task on the sixth bull of La Coquilla cutting off both ears. According to Corrochano, "...the crowd rushed into the arena. They squeezed him, took off his shoes, took him to pieces, like a reliquary. The guards intervened, always the guards, so that they do not kill him with rage or so that they do not get rid of enthusiasm and take it to bits like an afternoon's token".

He confirmed the alternative in Madrid a few days later with a very good reception. And it is that, he explained to his entourage, after leaving a square hit by pillows: "Every 100 afternoons, I prefer to be once well and 99 badly than 99 regular and once badly ".

Together with the second Gitanillo de Triana and Joaquín Albaicín they formed the poster of art, the shortlist of gypsies, which had its greatest success in Vista Alegre (Madrid), repeating itself in various squares in Spain and France. In La Coruña, the three fine bullfighters, with a bullfight by Miura to provoke excitement as a ticket at the box office, had a resounding failure. It happened what had to happen. Clarito titled his chronicle: "Three gypsies deceived 8,000 Galicians".

But Cagancho not only provoked the anger of the fans in Almagro, he offered similar performances in Calahorra and Zaragoza that same year as his alternative. The Aragonese bullfighting chronicler of this fair in 1927, according to what Mariano García tells us in "ElHeraldo", in the article "And Cagancho set up a scandal in Zaragoza", published on October 17, 2009, he wrote: yesterday in Zaragoza, after a performance of incomprehensible fear, freshness and ignorance, the entire Civil Guard of the province had to prepare to guard him at the end of the bullfight so that he would not fall victim to the wrath of a core charged with reasoned indignation. The cattle ranch was from Concha y Sierra and the performance was of the same tenor as in Almagro. In the first he gave a front puncture and, later, a pierced lunge. He went wild on the sixth attempt. The fifth of Concha y Sierra, was a pronghorn, handsome, cowardly and with looks and made of ox. He stabbed him across. Then another gore, Another ignominious prick. The first warning sounded. Another puncture and two attempts at pithing. A puncture in the neck, when the second warning sounded. He hit another puncture, and another, and... New intervention by the laborers, more punctures and... to the corral.

Surely among the insults that were dedicated to him, you would hear that phrase "don't prick him more than the skin is worth" because it seems that on these occasions Cagancho left his leather like a pincushion.

For his part, the dean of Catalan bullfighting journalism, Antonio Santainés Cirés, (1929-2014) in his article “Joaquín Rodríguez Cagancho: centenary of his birth”. Bullfighting Yearbook 2003, nº 37. Madrid Press Association, pp . 60-63) writes:

“The losing streak continues. Zaragoza goes to the Pilar bullfights. On October 17 [of 1927] he fights with Antonio Marquez and Gitanillo de Triana. The bulls are from Concha y Sierra. Already the day before at the end of his magazine, Don Indalecio said: "... And let's wait for tomorrow. Torea Cagancho. The ticket we got to see him, will he be a tenth winner? "Wow! Cagancho has been fatal. And in the fifth he heard the regulatory announcements and the ringing of the cowbells. The gypsy went to the infirmary but when Dr. Pérez Serrano certified that he was not hurt, the president suspended the fight, forcing him to leave the ring. After dark, Cagancho was able to leave the infirmary in the square dressed as a civilian in a car, leaving for Casetas to take the train. As a result of this event, "La Voz de Aragón" from Zaragoza published an original cartoon by Teixi [Luis Teixidor Cortals] that represented a mouse in jail, looking at a clock and commenting strangely: Eight o'clock, and Cagancho hasn't come! Joke, which with the expression "How rare, nine o'clock and Cagancho sinvenir", has been attributed to Xaudaró as published in Black and White in the 1930s. (Joaquín Vidal, Madrid - 01/02/1984, in EL PAIS). We reproduce here that of Teixi taken from the aforementioned article by Santainés.

Manuel Ramírez also reports, on the ABC of Seville on Tuesday, 7/14/1987, p. 56, that at the April 1929 fair in Seville, Cagancho was announced to fight three out of five afternoons. The first was quite bad. The second caused such a scandal that he had to leave the square protected by the security forces. Faced with such a situation, the Civil Governor, fearing that greater public disorder would be organized the following day, officiated at the company, forbidding it to fight.

Many afternoons like the previous ones the bullfighter must have lived. Many, he had to leave escorted by the Civil Guard and many, visit the cells for these reasons. Hence the aforementioned gossip and the allusive couplets that were sung like the following: "Don't come to the prison door to sing to me, Cagancho is asleep and you're going to wake him up." Such was the fame of throwing the bulls into the corral, of leaving them alive, that the bullfighting chronicler "Clarito" (Cesar Jalón Aragón, 1889-1985) in his "Memories of Clarito" (1972), tells that Cagancho, desolate, had just told him that their mutual friend Sabino had died suddenly and as he finished the cup of coffee, he appeared, Clarito exploded: "But damn your caste! Do you also let your friends live?"

But fame is not earned only by bad afternoons, and Cagancho, along with many such as those described, had sublime ones. We have already made reference to his triumphs in Mexico and Spain. If a bullring is named after a bullfighter, this is Las Ventas in Madrid, and Cagancho reaped notable triumphs there. It seems that the presentation of the novillero on August 5, 1926, together with Gitanillo de Triana and Enrique Torres, with steers belonging to the Marquis of Villamarta, large, with pitons and arrobas, was memorable with verónicas described as "enormous", "immeasurable". , etc. By the way, the bullfighting critic for ABC (E.P.), mentioned Joaquín Rodríguez and tacitly attached himself to the Catalan bullfighting critics, as he said, in parentheses, of his nickname that "I will never write the nickname of this bullfighter out of respect for the reader." From his great triumph, as opposed to the great failure in Almagro, the phrase that is sometimes heard, also, "Remain like Cagancho in Las Ventas", has remained, to indicate that he has turned out very well. The great bullfighting critic Gregorio Corrochanolo compared it in one of his chronicles with a carving of Montañés. He writes: "The black gypsy is dressed in white. Slowly like a ghost, he approaches the bull. With the stick of the muleta and the sword he makes a cross and thus this withered man appears to the crowd like a Carthusian, the color of the wood that chose for his carvings, the Montañés. The bull passes without the log moving and there is a noise of apotheosis in the spread. The left hand, bony or woody, peeks out darkly through the white sleeve sprinkled with gold..." and he adds: "That hand del Montañés, long, woody, which appears dark through the white sleeve sprinkled with gold, does some things of a bullfighter, with a cloying bullfighting flavor." And he ends his historical chronicle by saying: "I think Cagancho doesn't know how to fight, but when he fights... I felt a chill and crossed my coat."

The fame of Cagancho, the good one, passed from the chronicles to the letters. Federico García Lorca would write of him: «Joaquín Rodríguez“ Cagancho ”…monarch of gypsies» and Pedro Luis de Gálvez, (1882- 1940) immortalized him in one of his magnificent sonnets, a sonnet that ends with these two tercets:

“Feet together, upright, smiling,

Let the brute pass and indifferent

Look in a horn a golden flame.

The cañí has a torn jacket.

It's all the same... The plaza is in an uproar.

The envy a woman has of the bull!”

Among the many tributes in Spain and Mexico, the bullfighter from Triana has a tile in his honor on Calle Evangelista in the capital of Seville with this legend: “In the bosom of a family of singers, Evangelista came into the world at this end, a genius of art of bullfighting Joaquín Rodríguez “Cagancho” who brought the magic of the leprechauns of the cellar to the ring. He was born in 1903 and passed away on the last day of 1983”. And in Tarancón it has a street, Calle Joaquín Rodríguez Cagancho, which runs from Calle de Santa Quiteria to Cuesta de Barajas. There he fought several times. In one of them they gave him a medal of the patron saint, the Virgin of Riánsares, and while fighting a bull one day in 1928, he received a goring to the chest that could have been fatal, if that medal that he always carried with him had not deflected the horn. For this reason, he gave the Virgin a cloak and made various donations on other occasions. “From his pocket came the money with which the first X-rays were installed at the Santa Emilia Hospital” and he performed several times at festivals to raise funds for the poor of the town and for his hospital.

This was Joaquín Rodriguez Cagancho, the gypsy with green eyes, capable of invigorating the public in his inspirational afternoons and enraging them to the point of wanting to lynch him, in which the horned dance couple did not follow his steps. Almagro” is fatal, “To be like Cagancho in Las Ventas” is the opposite. I would settle for staying.

Madrid, April 3, 2021

6790 users have seen this newsOpinion| Grandstand