When Azucena and Florita were as popular as Captain Thunder

Seguro que al leer el titular muchos os habéis preguntado quiénes eran Azucena y Florita. Pues fueron dos de los grandes personajes del cómic español femenino que, en su tiempo, fueron tan populares como El Capitán Trueno. Desgraciadamente el cómic del Siglo XX también fue bastante machista, lo que acabó por alejar a las féminas de las viñetas. Hasta la actualidad, cuando grandes autoras y el fenómeno manga están volviendo a atraer a las lectoras. Pero esos cómics femeninos del Siglo XX también contribuyeron a que toda una generación de chicas aprendiese a leer y reflejaron los cambios de la sociedad española, como nos demuestra el libro Tebeos. Historietas para chicas, de la Asociacion Cultural Tebeosfera (ACyTediciones) que repasa los cómics femeninos del Siglo XX y es el tercer número de la colección Memoria de la Historieta.

Manuel Barrero, historian of the Spanish comic and director of Tebosphere, who turns 20, tells us why they wanted to make this book: “The comics addressed to the female audience have had the same consideration as the members of that audience: they have been removed fromthe history.For this same reason it is necessary today to avoid appealing to this type of publications such as "female comic", because a product and an audience that accessed comics in a natural and general way is being tagged but in reality the comic does not have a genre. "

"I explain," Manuel adds.Girls joined education and reading massively in the Spanish postwar period and read everything.They read thumb and possibly read the mask warrior (it could be said that no, but no one could try it) and, in addition, they read comics expressly made for them, but at first they were not so.The first “female comics” of the postwarMany girls interested in these publications and little by little they derived efforts towards a specialization of that type of press. ”

"The bad thing is that little was demanded," the historian continues.The collections of the first years were very careful, with excellent graphic finish, careful scripts, etc.Graphic approach was more static), a comic model "of using and throwing" ended in series.The most obvious consequence is that they became a mere product of consumption, ephemeral, not collectible. ”

"In fact, there are very few collections of this type of comics comparable to those of humor or adventure comics, because collectors have traditionally been men, men who proverbially were forced to" protect their virility "and men, inend, who unjustly forgot these comics for more sociological factors than typical of taste for good comics.Because there were bad comics for girls, but there were also very good ones ”-Manuel concludes.

15 years looking for female comics collectors

Study more than half a century of female comics has been a titanic job, as Manuel confesses: “Actually, the production of comics for girls, girls and young girls was so wide that, when studying it, which at first seemed easyIt became very difficult.A diachronic approach, that is, review each seal, or each stage or every thematic or stylistic current, would have been impossible.We decided to apply the same approach that we apply in the previous books of this same collection, comic memory: choose several key titles and work specifically on them.Thus, we have done thoroughly of Azucena, Florita, Blanca, Claro de Luna, Lilian Azafata del Aire, Mary "News", Jana, Gina and others, leaving aside hundreds and hundreds of other titles that were not less important, butwhich was impossible to address in a single book. ”

"We started from the idea that this type of comics had been little studied and that, when it had been done, it became very superficially," he continues.There are a good handful of articles about comics aimed at girls and little women, but few of them deal with the matter with rigor or knowledge, and as an academic reference we only had the book by Juan Antonio Ramírez, the female comic in Spain, dating from 1975.Notice that Ruth Bernárdez's book about the comic authors of the seventy and eighties (the girls are warriors), dates from 2018 ... There is a whole parenthesis there. ”

To make this book, Manuel confesses that he has spent 15 years looking for collectors from these women's magazines: ”There are two reasons to understand the difficulty of making this book. The main one, as I said before, is that the reference corpus is dispersed, you do not find it in the newspaper and is very difficult to achieve. In fact, we have been working on the great comic catalog for about fifteen years to try to shed some light on the collections for girls because we did not dare to address this study, because these collections were not well described. They have not been until a couple of years ago. And there are still lagoons. For example, we did not know that Azucena was published in parallel to the dissemination of three reissues, so there could be four comics of the collection every week in the kiosks simultaneously. We did not know that the AVE collection was twice as long as it was thought about twenty years ago, nor did we know that the last part of it consisted of the comics of the beginning, reissued with the changed covers to deceive the uninituted public buyer. ”

"Anyway, we didn't know about the existence of some titles and some of us still do not know," says Manuel.Look, as an anecdote (and scoop) I tell you the "grace" that made us discover that one of the first Spanish "graphic novels", the titled Maruja Sol, had been published in 1950 in a monographic comic as a unique launch, vertically, which Toray took out after having served by deliveries, within a fairy notebook, the dramatic story that is told in that comic.We discovered Maruja Sol the day after delivering the book to printing.Brrrrrr! "

"The second and great difficulty to make this book was to find those who would take care of writing the articles," says the historian.Who knows about comics for girls?Ask the majority of current comic critics and most will tell you that they know nothing.There are studies, such as Marika Vila, who read them for breeding and know them well, but several people who collaborated in this book had never read them before requesting their contribution.Others did knew them but had preconceived ideas about these comics.It has been difficult, but it has been very enriching, without a doubt. ”

Great authors and comics scholars

Among the authors that Manuel comments we find such interesting people as José María Conget, María Eugenia Gutiérrez, José Joaquín Rodríguez, Paula Sepúlveda, Isabelle Touton, Eva Sanjuán and Marika Vila."Tebeos.Recommunsixty to comment aspects of the industry;José María Conget is explained over the fifties, especially;María Eugenia Gutiérrez takes care of the sixties;Isabelle Touton, likewise, like José Joaquín Rodríguez and Paula Sepúlveda, who begin in the sixties and enter the seventies;Eva San Juan studies magazines from the seventies and eighties, and Marika Vila analyzes what happened at the end of the twentieth century. ”

"Each participant has chosen the approach he wanted to give to his analysis, there we have not wanted to establish premises," says Manuel.There are works that are made with a gender perspective, especially the last one, that of Vila, in which it reflects on the disappearance of this type of comics;There are others who use the theory of reception or sociological analysis, combining it with the gender perspective, and there are others that do not use it at all, such as mine, in which I stubbornly make a study on how that industry worked,a more empirical job. ”

"There is the myth that girls read fairy tales"

Now, that the comic has been submerged in a permanent crisis, it is difficult to think that millions of boys and girls read comics in the 50s, 60s or 70s. “The comics industry was powerful from the first economic impulse of Spain in theThe end of the fifties, enhancing greatly for a decade -Manuel says.This benefited the comics industry, which was extended in rolls and offer, but did so quantitatively, not qualitatively.A lost opportunity, because the editors, instead of investing in making better comics, did the same, multiplying them. ”

As for female comics: “The comic industry for girls experienced a similar boom-the historian confesses-and the editors discovered that there was a very high demand of such product.To such an extent that we have been able to demonstrate that there were certain stamps (Toray, Ricart, Ferma, Marco) that invested a lot of effort to edit this type of comics and that during a certain period they proliferated in the kiosks in greater numbers and variety than those addressed to an audiencemale (I mean adventure) ”.

"We cannot know how many readers were then because the democopic studies did not exist," says Manuel, "we can only intuit that, if an editor launched twenty weekly titles and more than half were for girls, then there was a female reading audience as abundant as themale for the products of that editor ”.

"There is the myth that the comics were a little thing and that they read few or circumscribed to" their "fairy and ñoñas stories," the author confirms.I think that is false.Since this industry started, in large part of the childhood comics that were published there was always a content offer for them, because the editors had the experience that girls also looked out of comic journals.All the big titles (TBO, Pulgarcito, Boys, DDT, Uncle Live ...), contained comics made for girls, because there was a potential reader audience integrated only by girls.Even in adventurous gender comics with magazine format we could find sections for them. ”

"It was different was the case of monographic comics, that is, those who only offered one thing (a fairy tale, a romantic story, an action adventure, a horror story), because in these cases the reader presupposed,"Manuel-.There were children who read fairy tales comics.Few, or many and hidden, because they exposed themselves to being accused of effeminate.And there were girls who read adventure comics.Not too many, given the possibility of being considered "marimachos."

"We don't know," Manuel concludes.But the comics of varied content were read both girls and boys, and I think there was no difference between some readers and others.The children's brain is as spongy in girls as in boys, and feeds on fiction with the same gratification.The only estimated difference may be that they did not collect them, but this was not due, surely, to their feminine condition, but to a series of social rites and a rigid education that was constantly redirecting the habits and behaviors of the girls, whileHe used to leave more freedom of action to the boys. ”

Did the comics contribute to settle a macho society?

On the stories of the female comics of the time, Manuel tells us that: “The themes of these comics were repetitive, it is incontestable that it was. But we must also recognize that the themes of the rest of the comics were very routine. The humor used to tell an anecdote, those of adventure a deed and those who occupy a fable. And they always told it in the same way. For some reason we seem to interpret that an adventurous story, which is always governed by the same keys, is "different" to a romantic story, which also contains fixed but different keys. But from the point of view of fiction consumption they are not so distant. In all, the final objective is the imposition of an order, that of social justice in the first case, that of domestic harmony in the other. In essence, they are similar to today's stories (those who go to a majority, familiar audience, those of the blockbuster movies, for example), although the behaviors of the characters and their starting status are very different. ”

As for whether the comics contributed to that macho society, Manuel says that: “At that time the society was androcentric and the comics transmit that idea, which we automatically associate that the comics for them pursued a specific purpose and the comics made forThey are another different.I do not believe that and I tell you in a personal capacity, of course, that other people who participate in this book could make another reasoning.I think that comics have never been tools at the service of a report that moves threads from unknown places, except when it has obviously created for that purpose.That is, there are propaganda cartoon, such as the one that was edited during the civil war, but already in the first postwar the powers linked to the State stopped producing those political vignettes and very few were the editors who inoculated some ideological soflama in their comics, simpleAnd plainly because that did not sell. ”

“The comics that sold well-Manuel adds-made them editors not linked to the Franco regime, whose cartoons were made by people of the plain people, most of them ideologically located in the antipodes of Francoism.Of course, all those products were macho, if you want.They were because the society in which we lived was like that, it maintained some inherited junctures of the old regime (not only from Spain, of the western world) that would take a long time to be modified, at least until the end of the sixties.The Spanish comics were macho as the Japanese comics were then (and now), as were the British comics at the time (and even), or as the Americans were throughout almost the entire twentieth century (andthey are)".

"If we asked your question otherwise," he concludes- answers on his own: did the American editors want to "impose the culture of a macho society" in the fifties?Did British comics transmit the conservative values of Thatcher imposing neoliberal culture in the eighties?The answer cannot be yes.In Spain, even in Franco's Spain, it cannot be yes.The comics seek to entertain and do so with the thematic deck and with the uses and customs of each moment.And what at that time was perfectly normal to be laughible, exciting or stimulating, today it can be interpreted (from a presentist perspective) as a racist, macho or even as a hate speech.But we cannot affirm that there was an intention to do so in that way to perpetuate a status quo.There wasn't. ”

"Florita had appliances that in Spain almost nobody possessed"

Pura Campos and other great artists of the time worked for the British and German market in comics that later arrived in Spain and that, sometimes, reflected more advanced societies than the Spanish."The comics that drew" Purita "Purification Campos were comics written by lords many times, such as Philip Douglas, who worked in the same way as the Spanish screenwriters," says Manuel.That is, she tried to build characters to seduce an audience and sell comics.It was the case of Patty (here, Esther) or Tina (here with several names), the series that made fields known. ”

"Actually, those characters were children of their time and did not challenge the tax order," he continues, "except for the youth rebellion they exhibited at some point.Obviously, British society was more advanced than Spanish in many aspects, but it was not especially permissive, much less with teenage girls. ”

"I do not believe that comics will contribute to modernize our society because for that many elements are needed, not only comics," says Manuel.In addition, our society should have already been modernized much earlier because since the fifties, little by little that editors imported foreign material were allowed, the Spaniards already exceeds how foreign societies were, especially the American.José María Conget comments it in his article, when he reminds us that in Florita magazine the characters possessed appliances that almost nobody had in Spain, or cars here impossible to drive.Reading these comics undoubtedly provided a magnificent evasive sensation, but I doubt that I contributed to change reality.Rarely fiction achieves it. ”

Claiming great forgotten authors

We ask Manuel if this book also serves to rescue great unjustly forgotten authors: “It serves to try to convince all those interested in comics and popular mass culture that this type of comics, even if they can be qualified as infraculture,They were important.They were very abundant and very read.They generated a lot of money for several editors and gave work to many authors, and what is more important: they supposed the mass entry of authors in the comic sector.Until then, the participation of women in the comics had been testimonial, and in fact a large part of the first collections of comics for girls always made men, both scripts and drawings, but then everything changed, perhaps because of the example of comfortGil, perhaps for the good smell of the editors of Toray or others, who understood that the participation of women benefited the reception of the product. ”

"We know that several authors were pseudonyms of male authors," Manuel tells us, "but many of these cartoons were made by women, of which we attest in the Catalog of Nico for Girls in the twentieth century, which is published as an annex ofthis book.And it has served to be more aware of the important presence of others, such as Rosa Galcerán, whose signature exhibited the editor as a way of selling her comics;or Carmén Barbará, which was a sales engine thanks to her fashion patterns;or Juli (Julia Sánchez Pereda), that everyone remembers as "a fairy tairseventy, generating a compact and solvent work. ”

"And we have located many firms that we know little or nothing, authors who have never remembered but contributed stories or drawings to an ever weighted industry," the author has added.I will quote some: Nieves Catalá, Nieves Francesch, Marisa G. Bone, Silvia Gema, Coral Lía, Mª Ángeles Arazo, Carmencita Soler, Angelita Tormo, Carmen Guerra, Merche Borrell, Marina Corrons, Marisa Fraga, Josefina Julbe, Carmen Levi, BlancaSanza, Mª Rosa Solá, Carmen Fraxanet, Marisa G. Bone, Carmen Levi, Josefina Sosa, Felisa Sánchez, Josefa Such ... and are just a handful of the hundreds of firms that passed through those comics.

The most important Spanish female comics of the twentieth century

We ask Manuel Barrero which ones believe that they are the most important Spanish female comics of the twentieth century: “This is easy: my girls, Azucena, Florita, Claro de Luna and Lily.

1) My girls, Magazine of Consuelo Gil, because it was the first title that showed that you could make a comics for successful girls.There was already one, the one entitled BB, which edited Buigas in the twenties, but had no continuity and did not differentiate much from any other newspaper for childhood!

2) Azucena, from Ediciones Toray, because he laid a success model that rushed to imitate the other editors, supported by very written stories and very attractive drawings, such as those of Rosa Galcerán, star and image of this notebook, which was with thewhich began and with which Toray ended his editorial career.

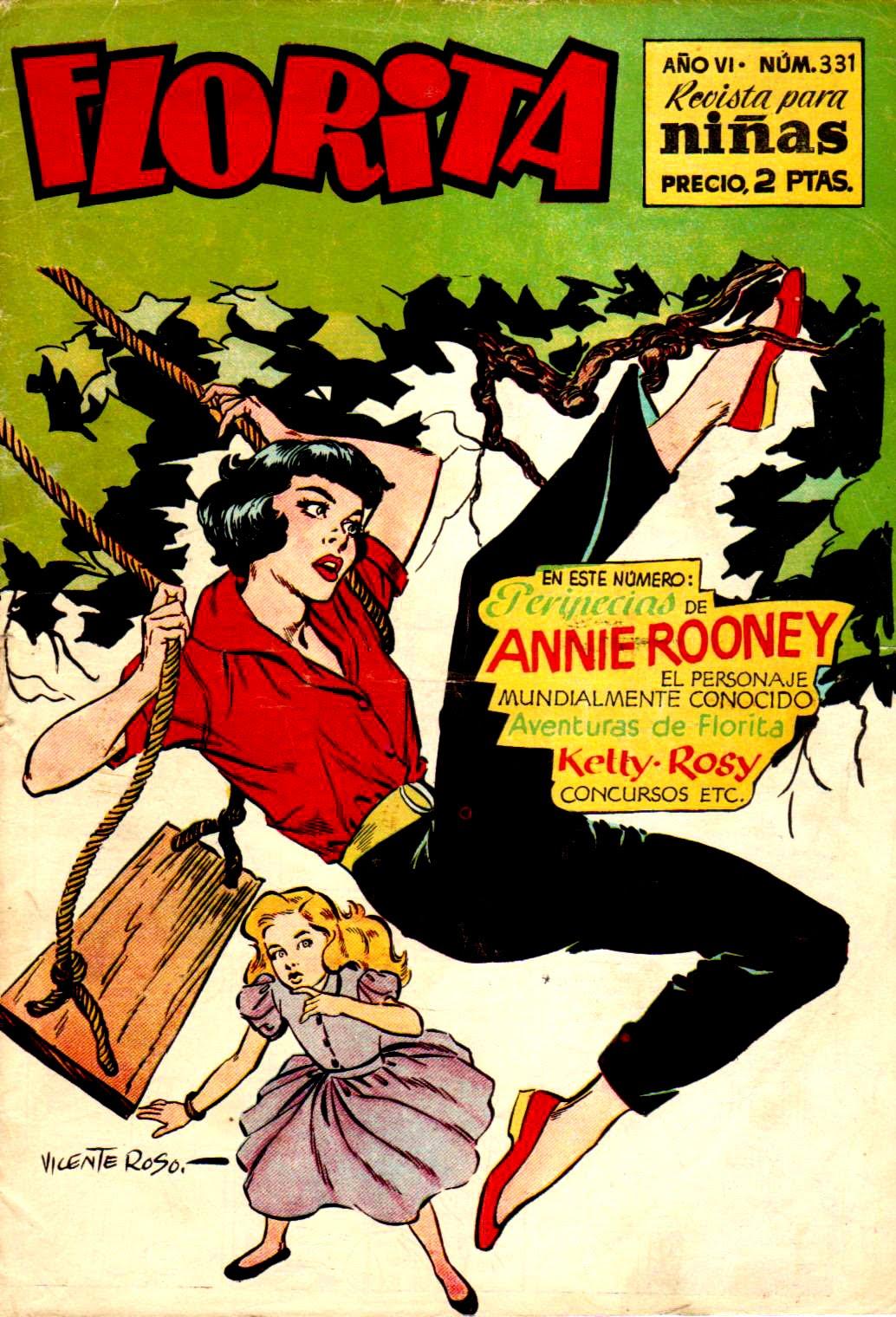

3) Florita, Clíper Magazine, an example of a well -made magazine, dense and sophisticated, with excellent authors, with cartoons translation from various countries and the first that was exported abroad in block, publishing in France as it was done in Spain (Mireille, who transmitted to the readers of France the same androcentric schemes that were consumed here, je).

4 Luna, from IMDE, because it was a publication that showed that comics readers joined the modern world, pop, fashion, that of contemporary society, while young male readers continued to evademedieval or parodies contexts in non -existent cities.

5) and Lily, from Bruguera, for being a very varied magazine, which introduced the Spanish girl in the Spain of developmentalism, and who gave her the adventures of Esther and her world, a British teenager with whom any young girl could be comparedSpanish, which explains its great success, which continues today in the Dolmen editions ”-Manuel-concludes.

By the way, we highlight the great cover of the book, of the National Comic Award Cristina Durán.

Tebeosphere: 20 years of scientific dissemination of comics

ComicsComics for girls is only the last of the essential theoretical works of Tebeosphere, an association that turns 20 years of scientific dissemination of comics."We celebrate it working," Manuel Barrero says.I had promised to lower the rhythm and that, when the twentieth anniversary arrived, this would already be sewing and singing.But not.On the contrary, we are working more than ever, because as you know we have wanted to celebrate a meeting of theorists that we have organized as a seminar on a specific topic: the comic theory.It was already celebrated, with great success, in Seville, the I Symposium of Comic Studies, in which we have reviewed all the theoretical efforts on cartoon developed in Spain, reflecting on this best theorists (Martín, Guiral, Altarriba, Pons, locked, Capdevila, Vila, dance and several more) ”.

“We also consider- adds- that our book Tebos.Comics for girls, it is a way to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the Tebeosphere project, because (and I do not lie) the book was one of our initial purposes, impossible to fulfill until two decades did not pass, since we did not have comics or knowledge enoughabout them".

As for the balance that makes these 20 years, Manuel says that: “The balance is by positive force.You just have to look at the figures at https://www.tebeosphere.com/catalogos/.We are the Spanish collective of comics that has generated more scientific literature, and in all knowledge plots, because we play all sticks.We have built a catalog of immense comics, although incomplete, but very enriched, to which all those who want to know something about comics end up going. ”

“And, most importantly, we have described the structures of our industry and also the presences of the authors who made Spanish comics.Our obsession in these last five years has been to improve biographical chips because they are the sap that nourishes this immense tree.I think that, in the end, all this work has given rise to a feeling of a good avenue that is very beneficial.That is, we have managed to convince many to participate in this adventure and the number of collaborators is higher than any other comic project that has previously developed in Spain. ”

"And we continue, because much remains to be done," Manuel concludes.Among our goals is to discover the elusive comics, which are in all times, and know as many authors as possible.It is a work that never ends and is still fascinating.There is entertainment for another twenty years, or more. ”