30 years after the threat of cholera: a meaningless persecution

Entre 1886 y 1887, la epidemia de cólera más grave que se registró en la historia de la provincia provocó entre 5.000 y 6.000 muertos. Y desató una verdadera caza de brujas en las calles. Algunos vecinos marcaban las viviendas de los enfermos para que en el vecindario todos supieran dónde se alojaba la enfermedad; o directamente las incendiaban pensando que así acabarían con el mal. Un siglo después, se repitió ese brote de estigmatización, pero en este caso, enfocado contra Bolivia y su pueblo: los nativos de ese país cruzaban el límite entre ambos país sin inconvenientes, a pesar de que las autoridades nacionales se cansaban de repetir que la frontera estaba blindada.

One of the first measures taken by the provincial authorities, precisely, was to close the local borders and ban the famous “tours” of purchases to that country.Then, after years of having lived in the hardest poverty that a person can imagine, the State worried about immigrants who came to work in this and other provinces and began to censor them to determine what their subsistence conditions and, ofstep, control whether they were sick or if in recent times they had not received visits from any relative.

The Tucumanos, due to this health crisis, also discovered that there was a human traffic of people for labor exploitation purposes.The capital municipality joined the "Crusade".The then mayor Rafael Bulacio announced that the train "El Norteño" from Bolivia would stop and disinfect and sign the passengers who descend in the capital.

"I'm never going to forget those years.I was just starting and I was doing very well.Suddenly, when news began from the cholera of Bolivia, the officials became very nervous and triedto the purchase of merchandise in that country just over 30 years ago."In those days trips were a true industry.Street vendors and whole families were traveling to buy clothes, appliances, watches, perfumes and food.The change from one to one favored a lot and you could buy very good quality things.Do you see this watch?It's a citizen, I bought it 30 years ago and I only changed the batteries four times, ”he said as an example.

“People from places affected by cholera are entering through the north without due sanitary control in the border area.With that serious reality, Governor Ramón Bautista Ortega was found yesterday when inaugurating a choleric center at the Trancas Hospital, ”published our newspaper.In the note, it was also recorded that “the head of the Executive Branwhereby he adopted measures to sharpen the road and sanitary controls in the Tala and Cabo Vallejo River.In addition, he decided that every person who arrives in the province must take the antibiotic who kills vibration, since some resisted doing so ”.

In a meeting he had held with the mayor Luis Andrade, different referents of that community told Ortega that the shopping tours continued to be made without any kind of problem.They also denounced that the majority of busClose the borders.“There were people who were in charge of making you a Trucho permission and you were going without problems.There was a lot of money at stake and nobody wanted to lose a penny.A contact was made and chau, to another butterfly thing, ”said Navarro.

30 years after the threat of cholera: the other health crisis

The scandal that unleashed was enormous magnitude.Miroli, who for his work done won national recognition and even a position at the deralal level, in addition to announcing that he would carry out an internal investigation to try to find those responsible for profiting with those illegal permits, quickly came out to clarify the situation."We cannot put casames at the borders and machine -groomed the suicides who go on a shopping tour to Bolivia," he said.“In 24 hours we got Tucumán's transport entrepreneurs to suspend trips, but we stumble upon another problem: interprovincial companies that scale in our city, do not have any restrictions.Moreover, one of them requested authorization to make seven more trips to Salvador Mazza.We estimate that there are 500 tucumanos who daily made that trip, ”he added.How was the problem solved?Some Tucuman companies were authorized to capture those passengers to make the trip with better health control.

Persecution

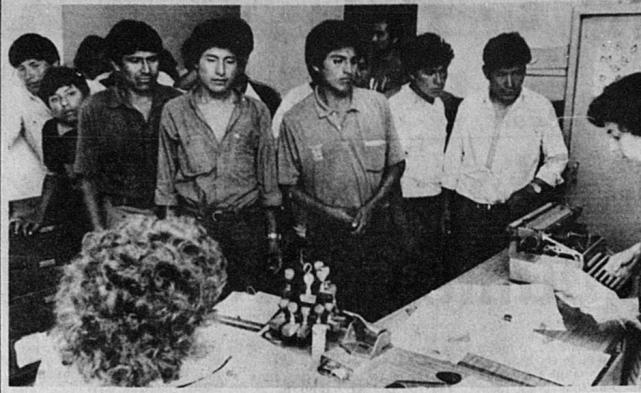

"A group of 23 Bolivian citizens who entered our country illegally was discovered and retained by the delegation of migrations in trancas and brought yesterday to this city," the Gazette published with a great deployment on Thursday, February 6, 1992, 1992."Immediately, Siprosa staff, headed by Dr. Matilde de Corzo, director of the East Central Programmatic Area, practiced people to verify whether or not they are affected by cholera, although they apparently do not present any symptomatic picture of the disease", it was added in the publication.

Detecting people from the neighboring country became a matter of state and, unfortunately, a police issue.Each operation in which immigrant workers were in the press.

"They were very difficult times.I arrived in Tucumán in 1990 with a group of compatriots.I realized that here I could have more possibilities than in my native potosí.I decided to stay and worked sun in sun.When I had the money, I paid the passage to my family to come.We were growing, first I was employed, then in charge.Then I lease and finally bought, ”said Hugo Condorí."It was impressive: I stopped leaving the fifth because every time the police did it questioned me," added the worker.

30 years after the threat of cholera: the evil of misery

In those days it was also exposed like the traffic chain of people for work purposes.La Gaceta, for example, reported an operation carried out by National Gendarmerie in Jujuy."That force discovered a new contingent.They were illegally admitted to our country in subhuman conditions to do rural work inside Argentina.Days ago, the same force had detected another ‘cargo’ of people who were subjected to a regime of virtual slavery, bound for Mendoza to lift fruits of the summer ”, could be read.

Always following the information published by this newspaper, the Gendarmerie authorities said that the new contingent was arrested immediately from La Quiaca.Within an old truck, covered by a thick canvas, 37 Bolivians were traveling without any personal documentation.The apparent fate were different Jujuy plantations, although the provinces of Salta, Santiago del Estero and Santa Fe were also mentioned.“The victims crossed the borders on foot for steps without permanent control and then were loaded in trucks.The Argentine authorities investigate in collaboration with the Bolivians, how foreigners accepted - or not - undergo an infrahuman work regime.It is suspected that there could be threats involved, ”.

In Trancas, another 30 Bolivian contingent was also discovered that had no documentation or medical certificate to indicate that they were not sick.The arrested trusted that a tucumano producer had hired them to perform tasks throughout the season (at least five months) for $ 500."It is not the first time I come to do these Changositas," said Pastor Gareca, originally from Tarija.

30 years after the threat of cholera

"The situation in our country was very complicated.The town was starving because the mines were closed and there was no job, ”said Esteban Mamaní.“It was said that in the north there was more land to work it.That with a little effort and good luck, in a couple of years one could access land, something that in Bolivia was impossible.And that was what happened.In the 80s the first began to arrive and in the 90s intensified.Today the country of countrymen is very large and, most of them managed to make their dream, ”said the son of an immigrant who came“ with one hand forward and another ”and now the family has land in Lules and Trancas."They were very persecuted by the issue of cholera.The municipal authorities for years turned their backs and, for fear of spreading the disease, they began to persecute them, ”he explained.

A problem

In the massive meetings that were held at the Government House, first the Vice Governor Julio Díaz Lozano and then Governor Ortega, summoned the mayors and communal delegates throughout the province to inform them of the novelties and ask for concrete actions in different situations.One of them, helps to detect the arrival of Bolivians.

"Everyone talks about cooperation, aid and union in newspapers, television and radios, but this delegation does not reach anything," said Ignacio Jiménez Montilla, who in February 1992 was the head of the National Directorate of Migration in our province, the agency that should attend all cases of Bolivians delayed in the province.

The official chose the Gazette to know the truth of what was happening in the province in those days.“It is being said that we had been provided with two means of transport to transfer the citizens of the neighboring country to the border, but it is not so.“Moreover, I no longer have funds in the body's small box because the transfers we pay for them.Our small box is $ 600 and daily we are receiving groups of 3 to 26 Bolivians and this also means expenses, since we have to feed them while they are retained, ”he said.

The official, in the interview, insisted that in this situation of health emergency that the country lives, and especially Tucumán, everyone must fight against cholera.“And I say this because the siprosa does not carry out any type of analysis of the Bolivians and is only limited to questioning them if they have symptoms of the disease.And I wonder: what will happen if some of these individuals were a healthy carrier? ”He insisted during the interview.“Many times we expel them and as we lack their own transport, they leave and then return, they wander.Some continue to travel to Mendoza and Buenos Aires and can generate the outbreak of the disease somewhere.The Tucumanos are not exempt from it: the danger is on the prowl, ”he warned in the interview.