Diamonds, gold, luxury homes: Inside a Los Angeles family's $18 million COVID-19 fraud

The Tarzana couple were returning from a Caribbean beach vacation last October when they ran into trouble.

On a layover in Miami, a passport scan flagged Richard Ayvazyan and Marietta Terabelian for further review. Customs agents took them away. They searched his luggage and phones.

Ayvazyan carried credit cards in the name of “Luliia Zhadko”. Terabelian had one that belonged to “Viktoria Kauichko”.

The FBI had been investigating “Zhadko” and “Kauichko” for months, following suspects, rummaging through garbage, poring over bank records. Agents suspected the names were aliases used to secure emergency pandemic loans to fake small businesses in the San Fernando Valley. Ayvazyan and Terabelian appeared to be part of a family fraud ring that was not very adept at covering its tracks.

After hours of questioning, they were arrested at 3 am and jailed for the rest of the night.

Thus began the unraveling of one of the most mind-boggling scams these US con artists staged last year, when the government rushed to send trillions of dollars in emergency funds to businesses hit by coronavirus economic shutdowns. Some would eventually turn on their own family members in a fight to avoid prison time.

Just three days after Congress approved an initial $2.2 billion aid package in March 2020, "Zhadko" signed up for a $112,000 loan to "Top Quality Contracting." The next day, “Kauichko” requested $150,000 for “Journeyman Construction”.

What followed was a torrent of loans to shell companies in the city that used stolen identities, falsified tax returns and fictitious payrolls to qualify for bailout money from taxpayers, court records show.

As of August, the group had taken out 151 loans mostly for fake businesses, some of them in real names. Fadehaus Barbershop raised $150,000; G&A Diamonds, $259,000; Red Line Auto Mechanics, $427,000.

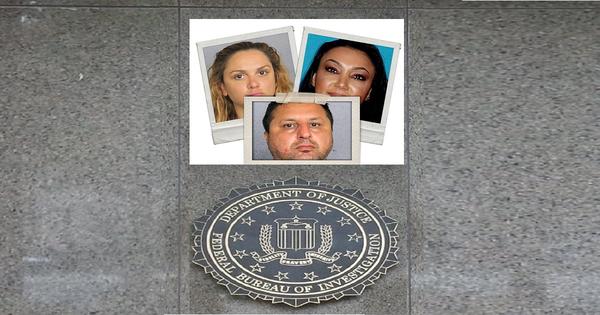

On June 25, a federal jury in Los Angeles convicted Ayvazyan, Terabelian and two family members of conspiracy to commit bank fraud, conspiracy to launder money and related crimes. Four accomplices pleaded guilty on the eve of the trial. In all, the circle of eight stole $18 million in emergency loans.

"That's a direct line to you: Everybody made money," Assistant US Attorney Scott Paetty told the jury in closing arguments. "Stolen money".

They spent it handsomely. In June 2020, Ayvazyan and Terabelian put $640,000 of pandemic disaster loans toward the purchase of a $3.25 million hillside home in Tarzana, a Mediterranean-style villa with a sweeping view of the valley.

Two weeks after the couple's arrest, the 2.6-acre property was the scene of a morning raid by FBI agents in combat gear.

As a SWAT team moved up the long, curving driveway in a convoy of trucks and Humvees, Terabelian, on bail, ran out the back door and tossed a bag into the bushes, prosecutors say.

“Hands up!” officers shouted, brandishing rifles as the pajama-clad children left the house with a dog and gathered on the pool deck.

The agents removed the bag from the bushes and emptied it. Piles of cash fell to the lawn, around $450,000.

At the conclusion of the trial, the jury decided that the government could seize the house, cash, gold coins, diamond earrings, wristwatches and other property purchased with pandemic business loans that were supposed to save jobs.

One of the watches was a $35,000 Rolex that Ayvazyan bought while vacationing in the Turks and Caicos Islands.

The family turmoil came to light when Artur Ayvazyan, 41, Richard's younger brother and a co-defendant, took the stand as a witness. He blamed much of the scam on his wife, Tamara Dadyan.

Dadyan, known as Tammy, a brash real estate agent with a penchant for calling people "idiots," had already named her husband and brother as two of her co-conspirators when she pleaded guilty to three felony counts in the loan fraud of COVID-19.

The core operations of what prosecutors called "an assembly line of fraud" took place at Dadyan's headquarters in the couple's home on White Oak Avenue in Encino.

In a search of the house, federal agents found a stash of fake driver's licenses and Social Security cards, along with fraudulent loan applications, checks and credit cards in the names of stolen identities.

Artur and Tammy's marriage was strained long before they called each other criminals. They slept in different rooms and were briefly separated, reuniting only for the sake of their two daughters, Artur Ayvazyan told the jury.

According to him, the lies occurred only on the Dadyan side of the house. He said he ran his own trucking and towing business, including an 18-wheeler and some tow trucks, and rarely ventured into his wife's office.

“I go there from time to time to make copies, faxes, that's all,” he testified. “I am very independent.”

When asked to explain the photos of the fake IDs found on his phone, he denied responsibility, saying “my wife probably” took them.

His attorney, Thomas A. Mesereau Jr., showed him a large number of handwritten documents seized from the home, some of which list stolen IDs used in loan applications.

“Do you recognize the handwriting on that document?” Mesereau asked over and over.

"Yes sir: it is my wife Tammy's," Ayvazyan replied.

His business was “devastated” by the pandemic, he pointed out, so he asked his wife if she could qualify for a government loan.

"She said, 'Yeah, I'll take care of it.' I replied 'Okay,'” he testified.

He claimed that Dadyan never showed him the applications he filed on her behalf with fictitious employee payrolls.

Once the loan deposits started pouring into his bank account, he stressed, it was more than he expected: first $10,000, then $125,000, and finally $150,000. He recalled spending part of it on truck repairs, tires and permits, but admitted he also bought a $24,000 Harley-Davidson motorcycle.

Under the Economic Injury Disaster Loan and Paycheck Protection programs, government aid could be used only to pay business expenses, such as payroll, rent, and utilities. He did not allow himself to spend for personal benefit.

Ayvazyan also admitted to sending $93,000 of his loan money to an escrow company to help his and Terabelian's brother buy his house in Tarzana. He said he was paying off some old loans from his brother, including one he used around 2009 to start a short-lived seafood business in Louisiana.

“I wasn't doing anything wrong to pay my brother back,” he noted.

Mesereau, who once represented Michael Jackson, urged the jury not to blame his client for his wife's wrongdoing.

"There is no blame in the United States because his spouse is corrupt," he stressed.

The jury found Artur Ayvazyan guilty on 21 counts of bank fraud, conspiracy and other crimes.

Following their federal sentencing, now scheduled for September, brothers Ayvazyan and Dadyan face state trial on mortgage fraud charges unrelated to the pandemic.

Rich and Art, as they are known in the family, were born in Armenia, when it was part of the Soviet Union. They spent their childhood there, then emigrated to the United States in 1989 with their single mother and 10 other relatives.

After settling in North Hollywood, the family moved to what Richard Ayvazyan once described in a court filing as "a pretty bad section of Van Nuys." His mother found a job sewing in a clothing factory.

The children did not speak English and endured a harsh adjustment in Los Angeles public schools. It took the elder Ayvazyan some time to realize that “a so-called Armenian friend” was deliberately mistranslating things as a joke.

After finishing high school, Ayvazyan got a job as a bank teller at a Wells Fargo branch. It didn't last long. At age 20, he was arrested for grand theft in a scam involving fake checks. He eventually broke into the real estate business, but his criminal record made it difficult for him to establish himself.

Ayvazyan met Terabelian at a party in 2001. They married a couple of years later and had three children. For a time, Terabelian ran a children's barber shop in Sherman Oaks.

Legal problems flared up again in 2011, when the couple was arrested for filing false tax returns to obtain a $500,000 line of credit on their Encino home. After they pleaded guilty to mortgage fraud, their lawyers, seeking leniency in sentencing, criticized the banks for their lax lending standards. Both were saved from jail.

“My purpose was not to make illegal profits, but to provide myself and my family with a good place to live,” Ayvazyan told US District Judge Cormac J. Carney in a letter.

"My own sense of guilt and shame for what I have done," he wrote, "is magnified a hundredfold when I look into the eyes of my children."

A decade later, the children, now teenagers, listened raptly from a courthouse bench as prosecutors presented evidence of their parents' misdeeds in the COVID-19 loan scam.

Much of it was based on text messages between her father and her aunt Dadyan. The typo-riddled dialogue between “Rich” and “Tammy” laid bare how the group exploited aid programs with ruthless efficiency to get loans before the money ran out.

In her plea deal, Dadyan admitted why they were texting: to use fake payslips and forged employer identification numbers to pass off their companies as legitimate.

In one text, Ayvazyan directed Dadyan to a loan website, telling him to go there "right now and apply because they are approving and closing within 24 hours." She advised him to set a single digit employer identification number (EIN) for each business.

"Just change your EIN to a number," she told him. "I made seven applications last night and four of them received an email saying they were funded."

When Dadyan asked Ayvazyan to “send me your payroll statement”, she mentioned an account he had opened under the stolen identity of “Iuliia Zhadko”.

“I used the bank statement I gave you for Iuliia,” she wrote. He continued to mock Wells Fargo's background screening of applicants: “They don't check shit, Tam. Everything is automated."

The group often used the names of Eastern Europeans whose identities had been stolen from visas while studying in the United States, prosecutors told the jury. Bank accounts were opened in his name, but controlled by Ayvazyan, Dadyan and their fellow fraudsters. The names were listed as bogus business loan applicants.

Even so, the inventiveness reached a certain point. Several shell companies submitted identical payrolls, claiming eight, 11 or 22 employees.

“They use the same numbers down to the penny, and they do it over and over again,” Christopher Fenton, a Justice Department trial attorney, told the jury.

Ayvazyan and Dadyan sometimes sent each other photos of fake loan applicants.

“Is this the face of a guy you used?” Dadyan asked Ayvazyan. “I didn't use this one, the one I have is the same one this guy changed the numbers on. I don't want to give everyone the exact same numbers."

"Don't wear all the same," Ayvazyan replied. I have like 3 different ones.

They joked about using the identity of a dead man in Armenia.

“Come on, the fool is dead on Armenian soil,” Dadyan wrote.

One of Ayvazyan's most brazen crimes was the theft of the identity of his wife's late father, Nazar Terabelian. Five days after the man's death in July 2020, his name was listed as the applicant for more than $500,000 in emergency COVID-19 loans for Mod Interiors, a fake business named after a real one.

More than $400,000 of that loan was spent on furniture, diamonds, jewelry and gold coins for Ayvazyan and Marietta Terabelian, prosecutors said.

A pandemic loan was also used to pay the $8,500 funeral bill for Nazar Terabelian's funeral.

In June 2020, federal auditors found something wrong with the loan applications submitted by “Zhadko” and others in Los Angeles: They were using similar types of documentation and fake IDs. The scale and carelessness of the fraud became apparent as investigators dug deeper.

Agents checked Encino's address that “Zhadko” noted on his $150,000 loan application for Time Line Transport. It was the house where Richard Ayvazyan and Marietta Terabelian lived, until they moved into Tarzana's house.

Investigators used bank records to track Time Line Transport's loan expense: Ayvazyan used $110,000 for a down payment on Tarzana's house. They discovered that his wife had also siphoned off the pandemic loan funds, about $250,000, to purchase the residence.

Federal agents tracking other COVID-19 relief loans discovered that $239,000 had been earmarked for “Zhadko’s” purchase of a $1 million home in Glendale. A review of the home's utility bills showed who was paying them: Terabelian's mother.

Closing documents for the Glendale home sale listed a dead man, Olaf Landsgaard, as "Zhadko's" attorney. And officers patrolling the property saw Dadyan visiting in a black Mercedes-Benz SUV that was registered to another Terabelian relative.

Federal agents traced even more pandemic loan money to a third home purchased in "Kauichko's" name, this time in Palm Desert.

When Geffrey Clark, a criminal investigator with the Internal Revenue Service, drove through the San Fernando Valley to check the business addresses the group listed on their loan applications, he found no sign of Journeyman Construction or Fiber One Media. He searched for Time Line Transport in Woodland Hills.

"The business wasn't there," Clark testified.

When Ayvazyan and Terabelian left for the Turks and Caicos Islands, prosecutors decided they had enough evidence to arrest them. Unaware that the scam was about to end, Ayvazyan texted Dadyan about “Zhadko” borrowing from the resort where he and his wife were loitering, along with a photo of the white-sand beach and deep blue waters. windswept turquoise.

Around the same time, Justin Palmerton, an FBI agent in Los Angeles, asked customs agents in Miami to detain the couple for questioning on their way home, a move that would later cause problems for prosecutors when a judge discovered that their phones were incorrectly registered at the airport.

The next morning, Terabelian made two quick calls to anonymous people from the Broward County Jail in Fort Lauderdale. Switching between Armenian and English, she asked for help hiring a lawyer and then made a clumsy attempt to cover up her family's misdeeds.

"Try to clean the house as much as you can," she said. "Everything".

If you want to read this article in English, click here.